In the city known as the “Jewel of the Renaissance,” young artists find inspiration, but little support.

The setting sun gleams off Raphael’s face. He stands 14 feet tall in bronze on a huge granite pedestal at the top of Via del Raffaello, the steepest street in the small Renaissance town of Urbino, his birthplace. World-renowned as one of the most important painters of the Renaissance, he still influences the city and its current artistic culture.

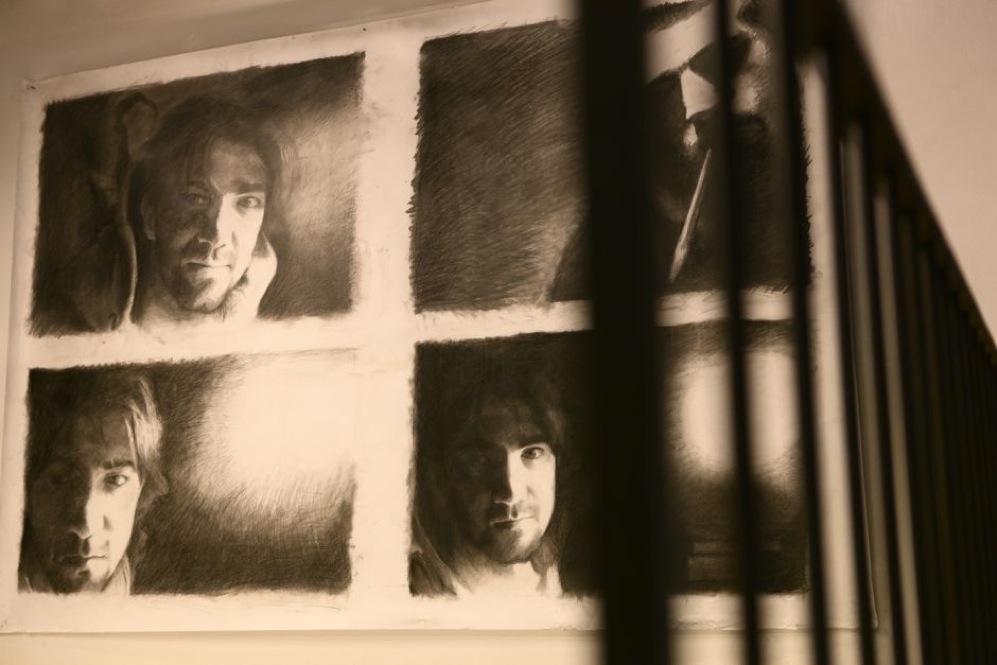

Down the cobblestone street in Raphael’s restored childhood home, Elvis Spadoni wears a wrinkled shirt and khakis that complement his shaggy hair and gruff beard. It is his first art show, and the house is packed with viewers captivated by this new artist’s traditional charcoal works. Each piece contains an aspect of Spadoni, as well as traces of Raphael and Michelangelo.

Four years ago, Elvis had never painted or sculpted. But thanks to the local fine arts academy, L’Academia di Belle Arti he has begun to master classical art. He is becoming increasingly well-known in Urbino, but it has been a struggle.

Spadoni was born in Urbino in 1979 and grew up in Casinina, a rural town close by. He was named after the King of Rock and Roll; his father wanted his child to have a unique name and his mother was a Presley fan. Elvis grew up drawing and sketching, but only as a hobby. He studied at a specialized school in Remini that concentrated on the humanities.

“We studied Greek, Latin, philosophy. . .nothing about art, very little,” he says. “But I found this background very, very useful.”

After high school, at 18, Spadoni attended seminary. For the next nine years he studied and served the Catholic Church in Remini and Bologna.

During his time in seminary, he was bombarded by ideas, thoughts that would eventually find themselves on paper.

“I felt that it was my best way to communicate, but only sketch,” he says.

Many of these sketches weren’t serious, but occasionally he produced a drawing that hinted at more than just lead on a page.

By the time Spadoni was 27, he realized he was not happy. Something was missing.

“My fear inside, fear to live life free, make me think that my way was to become priest, to serve the Church,” he says.

Within the course of two days of intense reflection, Spadoni left the seminary.

“We have to be what we are,” he says, referring to the inner turmoil he confronted at the end of his seminary days. With that realized, he returned to Urbino to start anew.

After passing an application exam, Spadoni began his studies at L’Academia di Belle Arti. The fine arts academy, build around a renovated convent, focuses on traditional arts as well as new and evolving media like video. Students of the academy, who range in age from 19 to more than 50, have close interaction with the professors.

“The contact with the professors is much more immediate, much more personal,” says Sebastiano Guerrera, who has been at the academy for 28 years, as a student, professor of paint, and now as the director.

“I can remember all my students by name. It’s a much more direct personal relationship than somewhere like Rome or another big city,” he says.

Walking around L’Academia di Belle Arti, Spadoni appears completely at home. The hallways boast an impressive array of student work, but around every corner is one of Spadoni’s creations.

“This is mine,” he says, motioning to a small bronze statue of Hercules as he walks down the main hall of the academy. Hunched over, the mythical hero stares from underneath the mantle of the Nemean lion that he famously hunted and slayed. Spadoni points to Hercules’s right index finger, which is missing its tip. Spadoni’s own finger is cut off at the same point, the result of a childhood accident with the gears of a honey-making machine.

“My favorite subject is myself. I’ve done a lot of self-portraits and even when I paint someone else I give him my likeness,” Spadoni wrote in a short essay about his artwork. “I think my style is narrative. My ambition, my desire is to use the painting, the drawing, the sculpture, to tell something.”

Continuing through the halls of the academy, he points out many more featured pieces along the corridors, until coming to a large canvas.

“This is my first painting for the academy,” he remarks nonchalantly. The image depicts Spadoni waking in a simple modern bedroom, and behind him is a replication of Michelangelo’s “The Creation of Adam.” The work is titled “Faithful to the Earth” and reflects the simultaneous distance and intimacy of man and God as a simple, everyday reality.

“To be faithful to the earth means to be faithful to the heart,” he says calmly. Spadoni resonates a similar simplicity and humility, yet the passion in his eyes is unmistakable.

“He’s a very diligent student,” says Marie Calajoe, a professor of technical languages at the Academy and the University of Urbino. “Whatever he does, he does it with maximum dedication. It’s as if he was born again and he’s discovering everything for the first time. He’s so open and absorbent in everything that’s around him.”

That diligence won him a six-week scholarship in New York through the Columbus Citizens foundation. He will be studying at various art schools around the state.

“For me, everything happens in New York; it’s like Disneyland,” Spadoni says.

Even though he is beginning to see the fruits of his labor, the past four years at the academy have not been easy for Spadoni. He continually struggles with whether he should work while studying at the Academy. Spadoni relates the burden of having a second job to the biblical story of David receiving Saul’s armor; David could barely move and so decided he could fight better without it.

“Someone give me an armor, I often take this, but in time I understand that I fall if I keep this armor.”

After having several jobs over the years, Spadoni has decided that the best way for him to learn and grow as an artist is to focus solely on his studies.

“The struggle is to follow your path,” Spadoni says. He has begun to forge that path.

Despite leaving the Church four years ago, Elvis says that he feels even more religious now. He sums up his decision as a “faithful experience of salvation.”

“I think God’s will is according to your nature,” he said.

That nature seems to be one of great potential, one that is only beginning in the town of Raphael.

“Urbino is like a big painting,” Spadoni says, of the beauty of the landscape and architecture. Although he derives a lot of his influence from Michelangelo, Spadoni says that as he has gotten older his appreciation for Raphael has grown. He says “the presence of Raphael” is always around and even though they are centuries apart, the two artists of Urbino have much in common.

“When I draw something like a face and an eye is crooked or the shading isn’t right and I have to do it over again, I think that centuries ago Raphael had the same problems.”

Spadoni is also beginning to see the same successes as his art style continues to evolve.

“I’m very interested in discovering a new way to relate to art languages, really like an old man observing a young man that is living his life.”

Slideshow

Click on Image to Show in Lightbox.

See Grant’s Video “The Barber of Urbino”