Moving Hips to Change Minds

- Hannah Chanatry

- On July 28, 2015

Professional dancers hope to change the popular Turkish view that belly dancing is for loose women.

Gigi Dilşa lives her life hiding in plain sight. She runs errands, says good morning to her neighbors, and goes to work, all while masking her identity. To some, she says she is an English teacher. To others, she is a personal trainer. But neither of these represents who Dilşa is nor what she does for a living.

Dilşa is a belly dancer and here in contemporary Turkish society, belly dancing connotes a woman of poor character.

The Turkish style of belly dancing emphasizes flexibility. Here, Gigi Dilşa takes time to stretch before her performance

“I cannot even say in my neighborhood that I’m a belly dancer,” she explains, sweeping on blue eye shadow as she prepares for a night’s performance. “I have to hide it, because it’s not accepted.”

The reputation of belly dancing in Turkey has fluctuated up and down with the current perspective taking a downward turn. But professional dancers are trying to raise that status, despite the pervasive stereotype in Turkish society that it’s vulgar.

Historically, belly dancing (or oryantal as it’s known in Turkey) was thought to be inappropriate for women due to namus, the cultural concept of modesty.

“A lady dancing was seen as a cheap woman, easy woman,” explains Professor Nilüfer Narlı, department chair of sociology at Bahçeşehir University.

This perspective eased in the 1950s when belly dancing began being performed in music halls, with shows pairing dancing and singing, and attendance dominated by couples. However this era was short-lived, with social tensions following both successful and alleged military coups pushing belly dancing underground.

“We had the army coup, and after that things got ugly, so belly dancing was affected with that too,” Dilşa says. “People started performing in nightclubs, nightclub dancers started wearing belly dance costumes, and it brought a bad reputation to belly dancing.”

That reputation is still coloring social opinion today. Under Turkey’s current government, belly dancing has been blocked on television, multiple venues that showcased belly dancers – some of them catering to tourists – have closed, and numerous people have stopped hiring belly dancers for weddings, a tradition that dated back to the Ottomans.

“It was about 10 years ago, they had this competition of belly dance, and it looked cute,” Dilşa says. “It wasn’t ugly or cheesy. Then people started thinking more positively about belly dance. But the current government is very conservative. So now it’s going backwards, and it’s going backwards very quickly.”

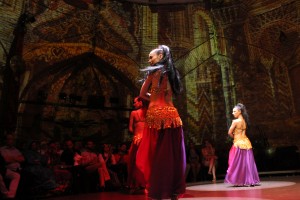

Dancers at Hoca Paşa perform during the Rhythm of the Dance show. Rhythm of the Dance celebrates both Turkish folk dances and belly dancing, by groups and soloists.

Yet pockets of society are pushing back against that trend, as people are turning to belly dancing for fitness and as a private activity.

According to Narlı, the 1990s marked the start of mass interest in belly dance education.

“There are many women learning belly dancing, and they go to workshops, training classes,” Narlı says. “This is only for their own personal satisfaction, personal growth.”

Professional dancers are often also teachers, and for many of them, this popularity provides an opportunity to spread an understanding of belly dancing so often misconstrued or ignored by the greater public. It brings people together, these dancers say.

“I see in my class a lady with or without a scarf, a lawyer, a normal student,” says Yıldız Hazel, a professional belly dancer and teacher through an interpreter. “When I see different people in the same room, I am thinking that, well, we are not separated. It makes me happy.”

Dilşa hopes continued interest in classes will one day change the way her profession is viewed in Turkey, dashing the assumption that the women dance for men.

“Belly dancing, when people really fall in love with the dance, when they aren’t doing it for money or attention, then they really see there is something in it for women,” she says. “It’s really for women to be connected and support each other. It makes them stronger.”

Erhan Ay spins during a solo belly dance performance. Male belly dancing is relatively common in Turkey, originating from its Ottoman history.

Video

© 2015 ieiMedia / All rights reserved