Cinema Nuova Luce

- Hailey Guyovich

- On June 25, 2014

Shining a new light on the old Italian tradition of serious filmmaking

URBINO, Italy – Tucked away on Via Federico Veterans, one of the cobblestone streets that wind through this hilltop city, lies a charming, one-room theater with the optimistic name Cinema Nuova Luce – Cinema New Light. It is open only on Tuesday and Wednesday evenings when Marco Lazzari’s projector lights the single screen with Italian and European-made artistic and cultural films. A “good turnout” is any time 11 of the 104 seats a filled, he says.

Meanwhile, on the other side of town, Cinema Ducale can seat about 800 people on its two screens showing the latest Hollywood blockbusters featuring American actors speaking in dubbed Italian voices.

This movie-going scene is the same across Italy.

“In my opinion, the real beauty of a movie lies in the simplicity and in the message,” he said. “I think Italian cinema has lost that a little bit.”

Once considered a world capitol of influential cinema thanks to groundbreaking works from legends such as Luchino Visconti, Federico Fellini, Michelangelo Antonioni, Italian films now largely mimic Hollywood movie-making, critics such as Lazzari contend. Italian move-goers, like their American counterparts, are no longer interested in the hard-hitting issues facing their country, he says, but prefer to be distracted by 3-D explosions, romantic comedies or fast-paced narratives.

Italian box office receipts support his case.

In 2013 the highest grossing Italian-made film here was Sole a Cantinelle, a light-hearted comedy by Gennaro Nunziane that collected $69.3 million. That same year, independent Italian filmmaker Gianni Amelio released L’Intrepido , a story exploring the despair ceated by in Italy’s economic crisis, generated only $1.5 million at the box offices.

That trend got world attention at this year’s Oscar Awards.

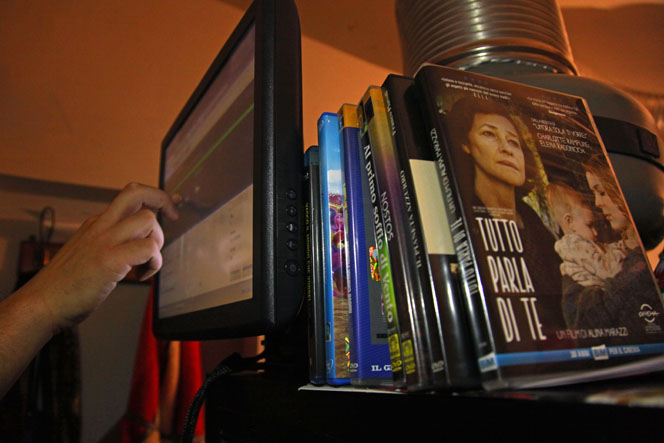

Marco Lazzari stands proudly during a demonstration of the highest quality digital film he owns, a far cry from what once lit up the screen when he was a boy watching his father run the theater.

La Grande Belleza (The Great Beauty), the internationally acclaimed art film by Paolo Sorrentino, won the Oscar for Best Foreign Film. Italy was apparently not as excited about Sorrentino’s release as the Oscar judges. La Grande Belleza grossed just $9.5 million locally, far out-paced here by a number of American films including The Hunger Games: Catching Fire ($11.1 million), Django Unchained ($16.2 million), and Frozen, the Disney animation, which raked in a whopping $26.4 million.

But Lazzari isn’t ready to join that new wave. He’s fighting with Cinema Nuova Luce to keep independent Italian cultural cinema alive in Urbino. Recent showings included Incompresa, by Asia Argento, and Le Meraviglieby Alice Rohrwacher.

Lazzari’s fight is actually a family tradition begun in 1950 when his fatheropened Cinema Nuova Luce and established the programming model featuring Italian and European artistic film. Marco inherited the theater at his father’s death in 2008 and feels no need to stray from that mission, despite the move by the majority of Italian moviegoers to contemporary cinema.

“From the beginning, the cinema only shows cultural films,” he stated with pride. “Nowadays [Italian filmmakers] tend to use a lot of special effects like in American movies. The young Italian filmmakers of today try to imitate American filmmakers like [Steven] Spielberg or Spike Lee. I don’t like that very much.”

Italian cinema dates back to 1896 with the release of Umberto e Margherita di Savoia a Passeggio per il Parco – “Umberto and Margherita of Savoy Walking in the Park by Filoteo Alberini.” But film historians say the golden age of Italian film was the first decades after World War II when Italian directors were leaders in the genre known as Neorealism, which exposed the ravages left by the war using largely nonprofessional actors on location. The stories often revolved around the working class picking up the pieces of lives shattered by the violence of war. Filmmakers were interested in documenting life as it really was as opposed to how they wished it to be.

Critics still rave about such Neorealism classics as La Terra Trema, Rome, Open City, and Bicycle Thieves.

Lazzari said one of his cinema’s missions is to show those cinematic styles to today’s audiences, especially the young. And he considers cinema to still be an active mode of cultural change.

“Teenagers love special effects and the 3D movies,” said Lazzari. “There are young people out there that prefer cultural cinema, but I would say 90 percent prefer the American movies.”

Leda Bartolucci, Federico Scaglioni, and Anais Piccoli are some of those teenagers that like art films – so much so they participated in a film program here at the University of Urbino. They consider most of today’s Italian productions “Saturday events,” and, like Lazzari, long for the days of Neorealism.

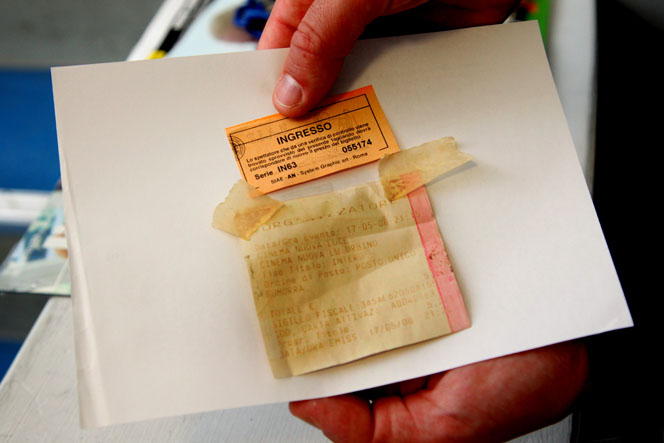

Photographs of Marco’s father that are kept at the front desk for Marco to glance at from time to time.

“I think cinema was something shared by everyone in Italy because we had some great directors and every work of theirs was a change in culture because it represented Italy as it was,” said Bartolucci, a petite and bright-eyed film enthusiast.

“The Italian directors that are popular now tend to show only what the young generation wants to see. It’s consumerism as opposed to an art form.”

Scaglioni said popular Italian filmmakers now try to emulate American cinema, a move which he says signals a loss of Italian identity in the field.

“Most Italian movies are comedies,” he said “Italians think a comedy is something like American Pie -something with a lot of sex and bad words. A lot of these films can be very fun, but there is no reference to real life.”

He said popular Italian cinema is repetitive, “Same stories, same actors, just a different place. With more tits every time.”

This shift in interest among the public has created many hurdles for independent filmmakers struggling to make a difference with their work, an issue Urbino filmmaker Andrea Laquidara understands firsthand. With productions fueled by passion but little financial support, the independent filmmaking industry can’t compete with the big-budget Hollywood films making their way to Italy, said Laquidara

“This is not a very happy period for our culture and cultural projects,” he said. “You have two options: to choose a commercial way or to direct documentaries or movies with particular meaning and language.”

Even then, Laquidara said, Italian filmmakers creating contemporary art pieces that will make a difference in the culture have a hard time getting their work shown.

This is where Cinema Nuova Luce comes to the rescue.

For inspiration, Lazzari keeps photographs of his father proudly posing with a new projector stowed in his ticket desk. He says he will continue to show the films both he and his father agreed are the most important – Italian-produced cinema rich in culture and artistic value.

Slideshow

Video

Order Urbino Now Magazine 2014

You can read many articles appearing on this website in Urbino Now Magazine 2014. To order a full-color, printed edition, please visit MagCloud.

You can read many articles appearing on this website in Urbino Now Magazine 2014. To order a full-color, printed edition, please visit MagCloud.Reporters

Can Aydoğan

Wes Casson

Olivia Condon

Katrina Delene

Klaire Dixius

Kylie Donohoe

Morgan Doss

Amanda Ellison

Victoria Ferris

Krista Flentje

Hailey Guyovich

Alli Kielsgard

Begum Kilicci

Meredith Kipp

Morgan Lynch

Olivia Lynch

Taylor Main

Olivia Martzell

Leslie McCrea

Kendall McNamee

Mary Menchel

Carson Monroe

Erin Mordhorst

Cori Noble

Urvi Patel

Kelsey Peck

Chris Raimondi

Summer Roberts

Whitney Roberts

Susan Rogowski

Jazmin Sahagun

Jamie Stotski

Landon Walker

J.J. Wilson

Promotional Video Project

Dimitri Daoulas

Jenna Fries

Cora Letteri

Abby Riggleman

Malorie Stone

Natasha Virdy

Story Categories

Past Urbino Projects

Read stories and view the photography and video from last year's website.

Read stories and view the photography and video from last year's website.

2013 Urbino Now App

Interactive Apple iPad app covering culture and travel for visitors to Urbino and Le Marche.

Interactive Apple iPad app covering culture and travel for visitors to Urbino and Le Marche.

2012 Website

Read stories and view the photography and video from last year's website.

Read stories and view the photography and video from last year's website.

2012 Urbino Now Magazine

Explore past coverage from the 2012 edition.

Read all 30 magazine articles online or visit MagCloud to order a printed copy of Urbino Now 2012.

Explore past coverage from the 2012 edition.

Read all 30 magazine articles online or visit MagCloud to order a printed copy of Urbino Now 2012.

2011 Website