Retroinnovazione - Urbino Project 2015

- Anita Chomenko

- On June 22, 2015

Learning about the art of cave-aged cheese from the Beltrami family.

CARTOCETO, Italy – Cristiana Beltrami was carefully approaching the cement-sealed mouth of a cave deep in the cellar of Palazzo Rusticucci when she turned to her visitors and whispered, “Shhh…the cheese is sleeping.”

She was serious.

Four months ago her father, Vittorio Beltrami, lowered 3,000 wheels of pecorino – sheep’s cheese – into the cave before sealing the entrance to allow it to peacefully age. When awakened by Beltrami it will be Formaggio di Fossa – cave aged cheese, a product the family creates annually.

Gastronomia Beltrami is a family business that sells only what they produce by hand – extra virgin olive oil, fruit preserves and cheese. Locals and tourists from across the Le Marche region drive on hilly roads to find the small, tree-shaded shop with the distinct smell of cheese wafting from the door.

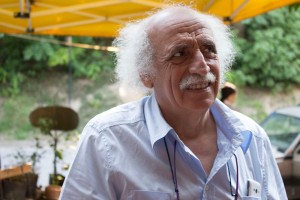

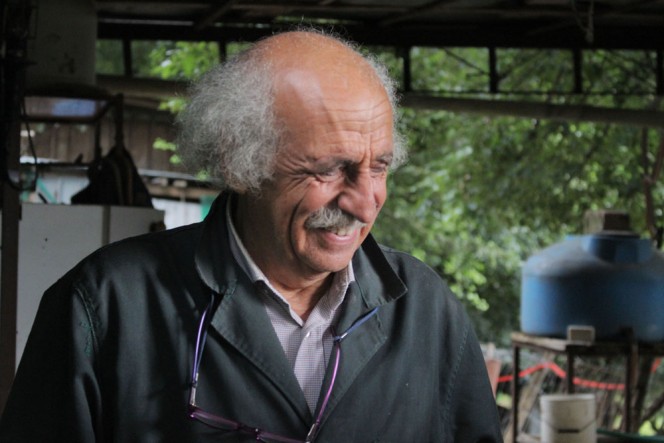

Vittorio Beltrami carries the nickname “The Einstein of Cheese” from American chef, television host and author Lydia Bastianich.

The shop is home to “The Einstein of Cheese,” a man whom American chef, television host and author Lidia Bastianich calls a genius.

This Einstein has white hair floating above his ears like clouds. Short in stature, he strides around the shop a short-sleeved blue shirt and his jeans slipping below his narrow waist. He stops his afternoon work to sit and talk with two visitors about his Formaggio di Fossa.

“Technology changes flavors,” the 66-year old Fano native said with fiery passion. “People don’t know how to eat properly, but I’m trying to teach them.”

Retroinnovazione, the family’s motto, is “innovation that looks to history to link the present first to the past and then to the future,” he said. “Then from that, to make something new.”

Their customers can sit on the front porch of the shop to try the different wines, olive oils and salami or bruschetta fresh from the brick oven. But Vittorio’s passion and true love lies with formaggio – experimenting with the milk from cows, goats and sheep. And the cave-aged cheese is his favorite.

Formaggio di Fossa was originally “created by chance” in the 18th century said Giuseppe Cristini, professor of Narratori del Gusto – Storytellers of Taste – at the University of Urbino.

Families in Le Marche and neighboring Romagna region used local caves to hide their food from Spanish invaders. When it was safe to remove several months later, they discovered the caves had made the cheese taste stronger – and better.

The wheels of pecorino are in the first stages of the aging process, resting in the upstairs cellar in Palazzo Rusticucci.

Cristini says Vittorio, his good friend, is a cheese expert, and a good friend. “He is a great observer and researcher in the field of cheese.”

Vittorio explained to his visitors there are many key components that contribute to the final flavor profile of a good cheese. He counts the steps on his fingers listing sheep, grass, a favorable climate, good milk – and timing. The sheep’s milk must be processed within three hours, then the aging process begins.

After the pecorino is created the cheese wheels are moved to Palazzo Rusticucci where they age, or mature, for four to five months in simple, open-air plastic crates. They are then put inside cloth bags and taken down the steps into the cellar to be placed inside one of the two caves.

Formed in the 17th century, the caves originally served as a refrigerator for a Cardinal’s summer home. Ice from the winter was carried inside to keep salumi, vino, olio and prosciutto preserved.

“Now the caves are used to mature the cheeses,” Beltrami’s daughter Cristiana said. Both caves run about 13 feet deep and maintain a temperature of 50 to 60 degrees.

The cave entrance is sealed with cement to prevent oxygen from reaching the cheese – and allow it to “sleep” for 100 days. On the last Sunday of November, Vittorio is not so gentle in waking the cheese – using a hammer to unceremoniously break the cement seal.

The cheese is carried back upstairs to rest in plastic crates again for 100 days before it is ready for sale.

Formaggio di Fossa is only produced once a year to allow the caves to breathe during the other months, Cristiana explained.

“Vittorio is an artist of food,” said Virginio Baldelli, owner of Osteria Da Gustin in Bargni. The restaurant is always offering a selection of the Beltrami’s cheeses for customers to taste.

“His cheese reflects perfectly the way we think about food,” Baldelli said. “It tastes like messages from the land, from Le Marche.”

After a full year of aging the pecorino, Gastronomia Beltrami is left with a golden-colored sharp cheese that Vittorio calls, the perfect example of Retroinnovazione.

Slideshow

Video (By Anita Chomenko & Dylan Orth)

Order Urbino Now Magazine 2015

You can read many articles appearing on this website in Urbino Now Magazine 2015. To order a full-color, printed edition, please visit MagCloud.

You can read many articles appearing on this website in Urbino Now Magazine 2015. To order a full-color, printed edition, please visit MagCloud.Reporters

Courtney Bochicchio

Christina Botticchio

Deanna Brigandi

Alysia Burdi

Anita Chomenko

Isabella Ciano

Rachel Dale

Caroline Davis

Nathaniel Delehoy

Brittany Dierken

Sarah Eames

Thomas Fitzpatrick

Kendall Gilman

Michele Goad

Julianna Graham

Yusuf Ince

Devon Jefferson

Rachel Killmeyer

Kaitlin Kling

Abbie Latterell

Ashley Manske

Rachel Mendelson

Alyssa Mursch

Manuel Orbegozo

Dylan Orth

Olivia Parker

Katie Potter

Gerardo Simonetto

Jake Troy

Stephanie Smith

Tessa Yannone

Ryan Young

Promotional Video Project

Nicole Barattino

Richard Bozek

Rebecca Malzahn

Abigail Moore

Charlie Phillips

Story Categories

Past Urbino Projects

Read stories and view the photography and video from last year's website.

Read stories and view the photography and video from last year's website.

2013 Website

Read stories and view the photography and video from the 2013 website.

Read stories and view the photography and video from the 2013 website.

2013 Urbino Now App

Interactive Apple iPad app covering culture and travel for visitors to Urbino and Le Marche.

Interactive Apple iPad app covering culture and travel for visitors to Urbino and Le Marche.

2012 Website

Read stories and view the photography and video from the 2012 website.

Read stories and view the photography and video from the 2012 website.

2012 Urbino Now Magazine

Explore past coverage from the 2012 edition.

Read all 30 magazine articles online or visit MagCloud to order a printed copy of Urbino Now 2012.

Explore past coverage from the 2012 edition.

Read all 30 magazine articles online or visit MagCloud to order a printed copy of Urbino Now 2012.

2011 Website