Vespa: As Italian as Pizza and Spaghetti - Urbino Project 2015

- Ryan Young

- On June 23, 2015

Urbino Vespa rally draws hundreds to celebrate the iconic scooter.

URBINO, Italy – Sunday mornings in Urbino, a historic town in central Italy’s Le Marche region, are typically very quiet.

Most of the locally owned shops and cafés that line the twisted cobblestone streets are dark. Only a few strollers walk through the Piazza Della Repubblica as church bells bounce off the blonde brick palazzos like they have since the Duke of Montefeltro made Urbino a center of Renaissance art and culture 700 years ago.

But this Sunday morning in early June, things were different. The usual quiet had been replaced by the buzzing of hundreds of two-wheeled motor scooters lining up just outside of Urbino’s Ducale Palace.

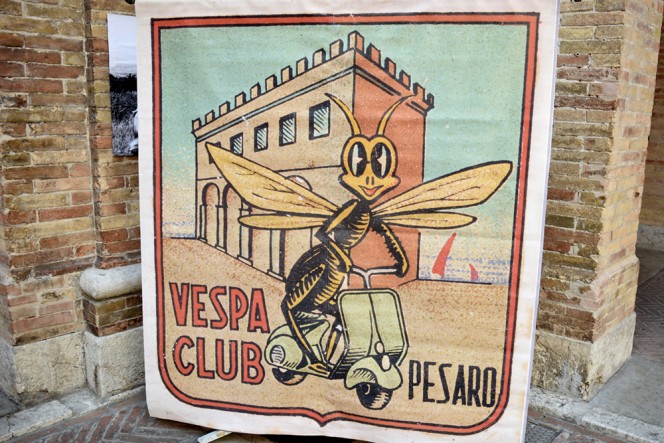

They were Vespas, the iconic Italian motor scooter whose owners had rolled in from all corners of the country, packing into the archway leading from the walled city.

“The Vespa for an Italian is like pizza and spaghetti,” explained one rider, Gabriele Cavalli . “Pizza, spaghetti and Vespa.”

This is a Vespa rally, a fairly typical scene in Italy. Just as a Harley Davidson motorcycle is one of many icons of life in the United States, Vespas are a cornerstone of the Italian culture.

Rallies like this have been common across Italy for decades. The two-day event started with an exposition featuring Vespas dating back to the early 1950s, giving visitors the chance to view the original iconic scooters. The second day offered a 43-kilometer ride through the Italian countryside, showing off the region to almost 400 different riders.

And by simply looking at the Urbino Vespa rally, one can easily tell that the scooters are still thriving today.

“It means that Vespa fans still exist,” said Riccardo Costagliola, the president of the Piaggio Foundation. “They are here, even youngsters like to have a Vespa, because it is a symbol of their heritage…It’s very important because they keep alive the culture.”

The very creation of the Vespa came from a need to keep Italian industry and culture alive.

The end of World War II was a devastating time for Italy, one that left many cities damaged or destroyed.

And with the industrial base largely gone, there was a need for an economical motorized vehicle: And the two wheeled Vespa arrived.

“The Vespa was born in a very sad moment for Italy,” Palma said. “Italy gets out of the war in terrible condition: poor, devastated, in need of being totally rebuilt. But as often happens in history from the darkest moments come out great events.”

The Piaggio Company, which specialized in aircraft carriers before the war, now had to switch gears to survive. Seeing a need, Piaggio focused on what they called personal mobility in 1944. Engineers envisioned as a simple, inexpensive two-wheeled motorized scooter, similar to an American moped or small motorcycle of today.

By 1946, they unveiled the first Vespa – Italian for wasp. Just 44 inches tall and 70 inches long, the single-cylinder engine gave the first Vespa a maximum speed of 37 miles per hour. The product was perfect for a population with little money to spend in a nation without the industrial base to build larger or more complicated vehicles.

The Vespa was an instant hit, selling almost 20,000 vehicles in just two years. And once these scooters hit the market, the Italian people fell in love.

“If you look at one of the first models, it was already extremely elegant, modern,” Palma said. “With the time, it only evolved…The Vespa, in that time, represented the joy of life, a reason to start again with new solutions.”

Vespas today can cost close to $7,000 and can travel much faster – up to 80 miles per hour. But in the 70 years since the initial launch, the design of the Vespa has stayed basically the same, even as the technology improved. This, Costagliola says, is what makes the scooter special.

“The Vespa is a Vespa,” Costagliola said. “Years after years change everything [else], but a Vespa is still a Vespa. If you see a scooter driving on the street, ‘Oh it’s a Vespa. Which kind? I don’t know, but it’s a Vespa.’ There are very few vehicles in the world with this ability.”

But it’s not just new Vespas that are hitting the streets today. Old scooters, even some from the 1950’s and 1960’s, are still in very good condition. Palma said that is an indication of both their initial high quality, and how deeply people care about them.

“As back then, even today the Vespa represents an object of worship,” Palma said. “It’s not something you can destroy or let get ruined. Therefore all the people that have a Vespa, they fix it up because nowadays the Vespa represent our own culture, which is the culture that has its roots in the Renaissance.”

The Vespa has long been a passion shared by entire Italian families, too. Cavalli traveled all the way from San Marino with his early 1950’s vintage scooter for the rally that he said was handed down from his grandfather.

“The Vespa is something you hand down, it’s a culture,” he said. “Then there are people who buy it because they like it. I brought the original one [to the rally], a vintage one. Then there are people who customize. I prefer to keep as it was because it is related to the culture”

While the scooters initially thrived in the 20th century, Costagliola said that he believes the Italian people will continue to go back to their roots and refuse to let the Vespa die out.

And after watching hundreds of men, women and children, both young and old ride through central Italy on that Sunday morning in early June, it’s easy to see how that prediction could be true.

“I think when [there are] periods of turbulence and periods of uncertainty, people stop and watch back to their past values, and Vespa is one of them,” Costagliola said. “It’s a piece of the story of the family and of the country, so I think the culture will continue.”

Slideshow

Video

Order Urbino Now Magazine 2015

You can read many articles appearing on this website in Urbino Now Magazine 2015. To order a full-color, printed edition, please visit MagCloud.

You can read many articles appearing on this website in Urbino Now Magazine 2015. To order a full-color, printed edition, please visit MagCloud.Reporters

Courtney Bochicchio

Christina Botticchio

Deanna Brigandi

Alysia Burdi

Anita Chomenko

Isabella Ciano

Rachel Dale

Caroline Davis

Nathaniel Delehoy

Brittany Dierken

Sarah Eames

Thomas Fitzpatrick

Kendall Gilman

Michele Goad

Julianna Graham

Yusuf Ince

Devon Jefferson

Rachel Killmeyer

Kaitlin Kling

Abbie Latterell

Ashley Manske

Rachel Mendelson

Alyssa Mursch

Manuel Orbegozo

Dylan Orth

Olivia Parker

Katie Potter

Gerardo Simonetto

Jake Troy

Stephanie Smith

Tessa Yannone

Ryan Young

Promotional Video Project

Nicole Barattino

Richard Bozek

Rebecca Malzahn

Abigail Moore

Charlie Phillips

Story Categories

Past Urbino Projects

Read stories and view the photography and video from last year's website.

Read stories and view the photography and video from last year's website.

2013 Website

Read stories and view the photography and video from the 2013 website.

Read stories and view the photography and video from the 2013 website.

2013 Urbino Now App

Interactive Apple iPad app covering culture and travel for visitors to Urbino and Le Marche.

Interactive Apple iPad app covering culture and travel for visitors to Urbino and Le Marche.

2012 Website

Read stories and view the photography and video from the 2012 website.

Read stories and view the photography and video from the 2012 website.

2012 Urbino Now Magazine

Explore past coverage from the 2012 edition.

Read all 30 magazine articles online or visit MagCloud to order a printed copy of Urbino Now 2012.

Explore past coverage from the 2012 edition.

Read all 30 magazine articles online or visit MagCloud to order a printed copy of Urbino Now 2012.

2011 Website