Queen of Arles Amélie Laugier waves to the crowd within Le Théâtre Antique before giving a speech in Provençal.

Text by Bella White

Photos by Sarah Naccarato

Forty-three years ago, Odyle Rio looked at the Arles local newspaper and saw a problem. The newspaper was named Le Provençal, but the paper did not publish any stories in her beloved regional language, Provençal.

Rio, harnessing the strength of her culture, challenged the director of Le Provençal. “He said if you want some Provençal in it, then you do it,” Rio said. And so she did. Ever since then, she has sat down every week to write a column for publication in what is now called La Provence. She chooses not to be paid and enjoys the freedom to write about the local topics that interest her.

Described by members of the outlet’s staff as the soul of the city, she writes in simple, spoken Provençal so that even people without a literary knowledge of the language can understand it.

The language, spoken particularly by people in the southeast of France, is classified as threatened, with only about 200,000 native speakers worldwide, according to the Endangered Languages Project.

Yet, Rio insists that Provençal is very much alive, and she is not the only one. While the life of the ancient language still has challenges ahead, many young Arlesian people are embracing the Provençal language and the culture as their own.

Local schools

Arlesian schools offer opportunities for students to engage with and learn Provençal. Students are introduced to the regional language in primary school and then given the option to pursue it as an elective in middle school. Students can even choose to do an additional specialization on their baccalaureate, or high school diploma, in the language.

By taking Provençal, students can also earn extra points on their national exams. For one regional student studying at College Charloun Rieu in nearby Saint-Martin-de-Crau, that served as her incentive to continue pursuing the language beyond middle school.

“I liked the lessons,” Aaliyah Murria said. “I did it just to do an option, and, because, for exams, it gives us points.”

Since Provençal teachers are few and far between, Murria and her classmates often go long periods without instruction.

Marie-Rose Guérin is a local Provençal teacher at two middle schools, College Frédéric Mistral and College Robert Morel, and a high school, Lycée Pasquet in Arles. She typically educates students ages 10 to 17 but teaches adult classes as well.

She is one of two teachers in the region who have a special certificate, Certificat d’aptitude au professorat de l’enseignement du second degré, to teach Provençal.

Nationally in France, language is a highly politicized topic. The French government banned regional languages from being taught and spoken in public schools until 1951, instead mandating French as the language of the republic. Even beyond that, French is mandated in commercial and workplace communications.

Learning Provençal “is an option,” said Frédéric Imbert, the 7th deputy mayor of Arles, whose portfolio includes education. “It’s a private decision of the family. This is not an organization of national education or the town. This is a choice of family.”

As languages like Provençal and Breton are in danger of going extinct, activists have become vocal about the inclusion of regional languages in public education. The Ministry of Education allowed the possibility of immersive teaching of regional languages in public schools in 2021 with the passage of Molac’s law.

“We’re all French, but each region has its particularity, and there’s a richness in that,” Guérin said. “So, it’s wonderful to be able to say to this centralizing power, ‘Yes, we’re French. But we’re also Alsatian or we’re also Breton, and we’re also Provençal, because these languages are actually what made French.'”

While some fear this progress is not enough to stop the regional language’s extinction, Guérin remains hopeful. “As long as the administration accepts that it can be taught, then I’m optimistic,” she said. “It’s fascinating to watch young people enjoy learning it because it’s not necessary. Culture is not ‘necessary,’ but young people seem to want to also carry it on to the next generation.”

Local culture

Schools, though, are not the only way that students can engage with Provençal. Local festivals such as the Fête du Costume, a parade held every first Sunday of July to renew Arlesians’ commitment to Provençal traditions, and the Feux de la Saint Jean, a summer solstice festival that honors a flame from a faraway Mount Canigou, offer young people a window into their community’s rich culture, history and dialect.

One student, Chloe Cauvin, chose not to continue learning the language after primary school, but she still interacts with Provençal culture through her family and their participation in local traditions in Saint-Martin-de-Crau.

Amélie Laugier, queen of Arles, was 3 or 4 when she first wore traditional Arlesian dress. Since no one in her family was wearing the traditional costume, she asked her grandmother, who owned a dress shop, if she could dress for the springtime festival in her home of Saint-Martin-de-Crau that year.

Now, 22 years old, she is one of the strongest defenders of Arlesian culture and language.

“It really is sort of a little girl’s dream,” Laugier said. “When you see the queen of Arles all dressed in this beautiful white costume, it’s very motivational. In terms of the first time feeling connected to the culture, it’s sort of a love that grows inside of you, that you can’t explain, and it’s a love of the costume, of the traditions. It’s not something you do for fun. It’s really something that comes from inside.”

There are several organizations in the Provence region dedicated to preserving Provençal. In small towns and villages, these organizations are uniquely situated to keep the traditional Provence culture and language alive.

“People learn about different events, different clubs, different organizations, sort of these folklore groups or traditional groups,” said Rémi Vénture, director of the Médiathèque, Arles’ public library. “It’s more about local grassroots movements that are getting more young people into it.”

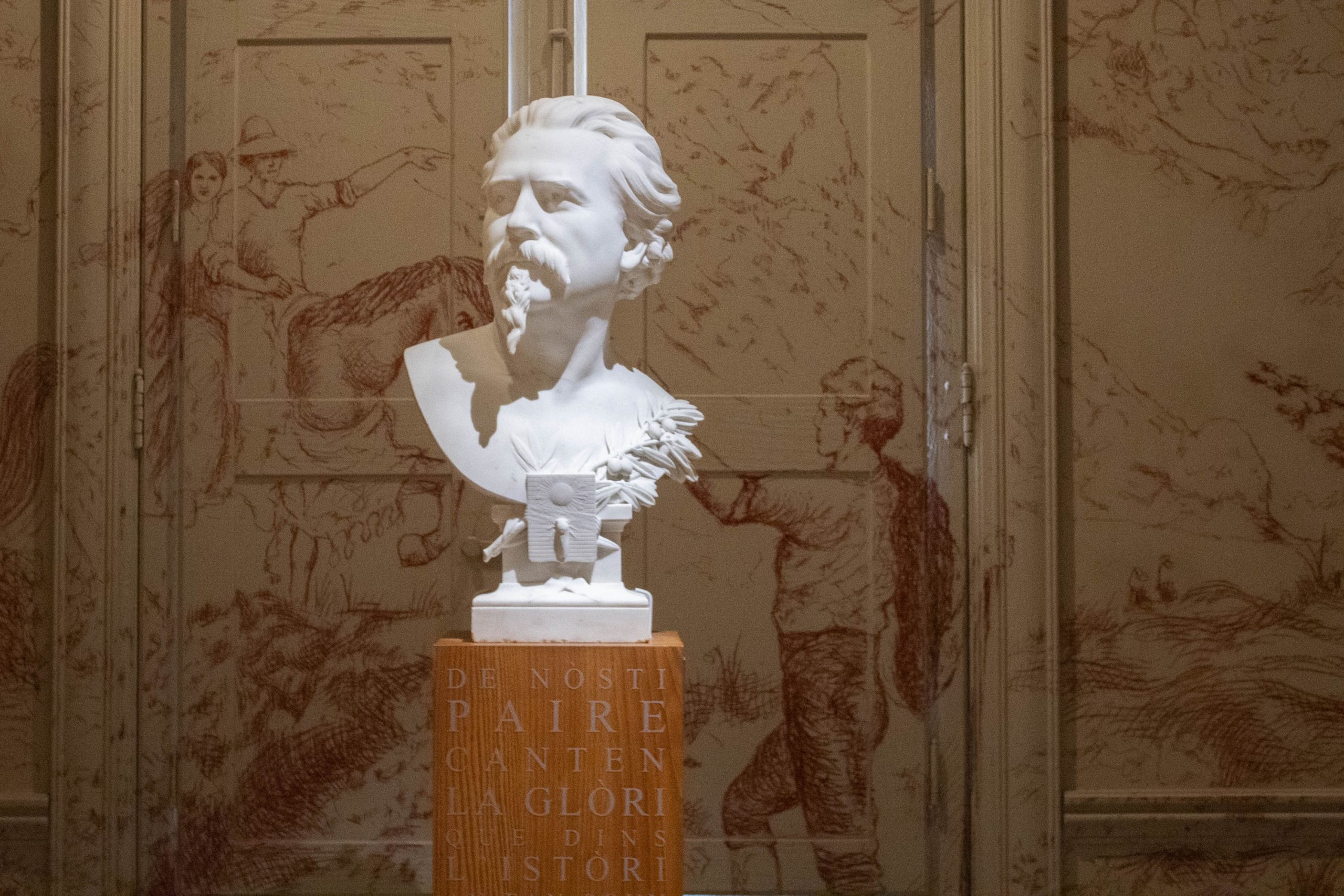

One such organization is the Félibrige. This 171-year-old Arlesian cultural organization maintains the rich and complex cultural history that comes from the Provence region.

“My language is my life,” Rio said. “When I’m dressed as an Arlesian, I have this strength in me, and I could go and speak to the president of the United States or the queen of England.”

Founded by Frédéric Mistral and five other Provençal poets in 1854, the organization has preserved the regional dialect amidst the national standardization of language in France following the French Revolution. Mistral, who was Arlesian, was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1904 for his work during his time with the Félibrige. His efforts significantly helped Provençal gain literary and linguistic recognition and survive into the modern day.

The Félibrige organization still continues this founding mission. Anyone who is highly motivated and can find a member willing to sponsor them can join the Félibrige and defend the Provençal language and literary traditions. Rio, Vénture and Laugier are among them.

“The language is continually evolving,” Laugier said. “I’m not worried about it continuing a long time into the future, mainly thanks to the Félibrige organization and the fact that they’re also using, for example, social networks to communicate, to put out videos, to allow more and more people to discover Provençal.”

Katie Thornton, Laird Harrison and Chloe Cauvin served as interpreters.