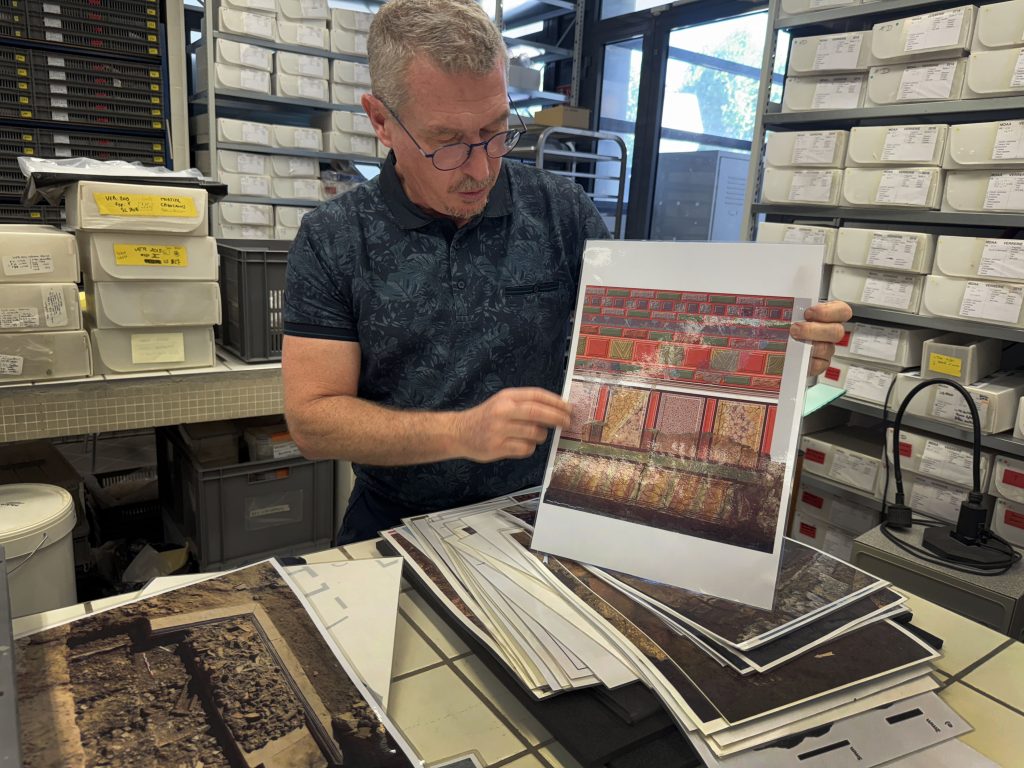

Archaeologist Alain Genot shows a reconstruction of the fresco painting.

Text and photos by Keri Azevedo

Buried beneath two millennia of dirt, debris and newer buildings, the Harpist of the House of Aïon in the Trinquetaille district of Arles, France, had been lost to the sands of time.

When the rare fresco came to light in 2015, its image of a woman carrying a musical instrument immediately caught the archaeological world’s attention because so few ancient Roman wall paintings exist in such complete condition.

“Although the wall was fragmented, with missing pieces, we can consider the state of its conservation exceptional, since the discovery of a painted wall still upright is not a common thing,” said Marion Rapilliard, a restoration specialist at the Museum of Ancient Arles and Provence, in an email.

Now, Rapilliard and the rest of the restoration team hope to perfect techniques to preserve the bold, red cinnabar paint that is dominant in this fresco and others like it. The Arles team’s innovations could lead to more ancient frescoes being available for viewing by the general public throughout Europe

The Trinquetaille site first attracted interest in the 1980s when archaeologists unearthed the 18th-century Great Hall of Glassworks. Little did they know that the deeper they dug, the more fruitful and historic the site would become. With each new layer exposed, soiled windows of the past became clear, revealing fresh insight and timelines to life in Arles.

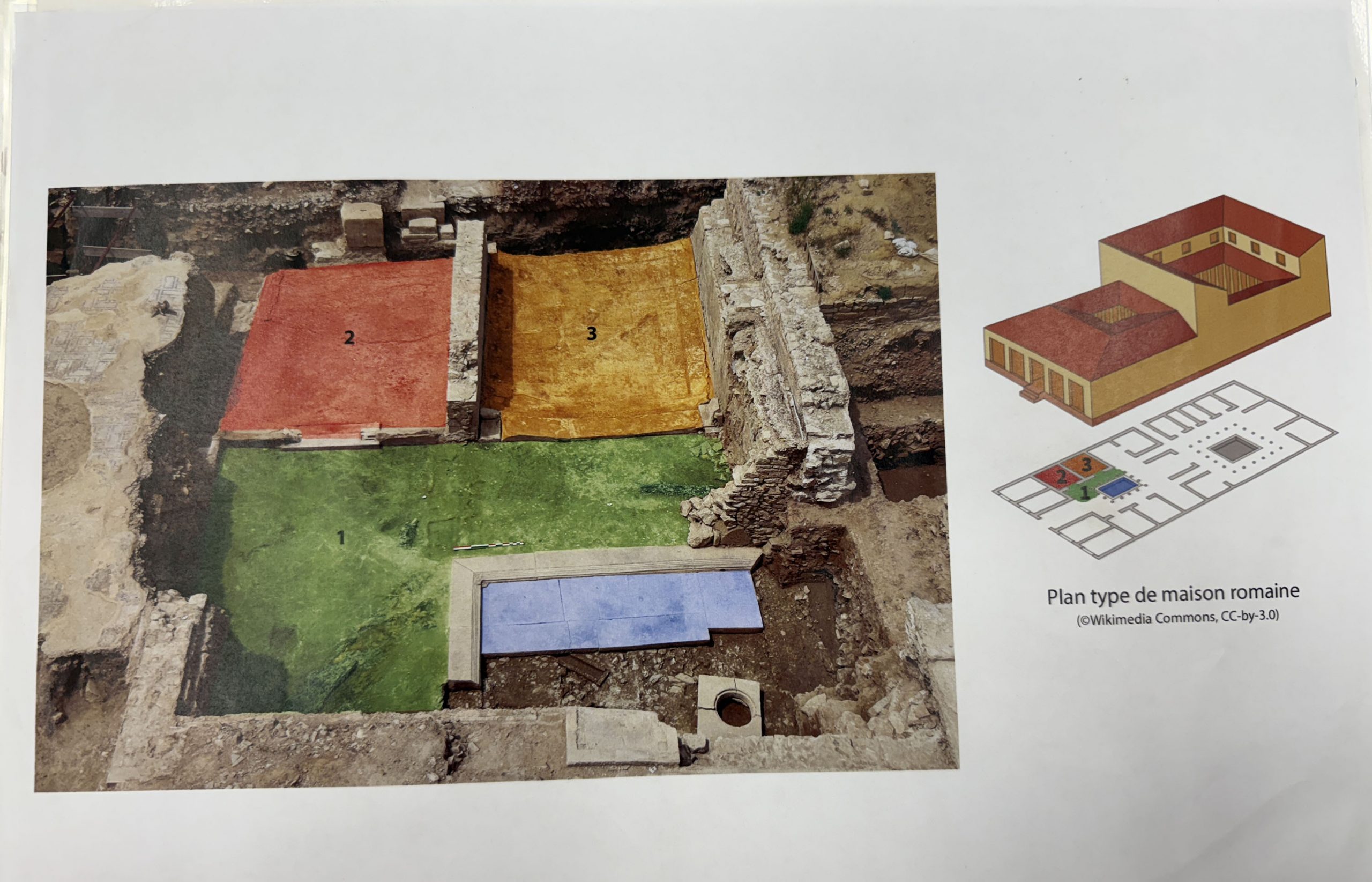

When excavators reached the House of Aïon, which dates between 70 B.C. and 50 B.C., they found a number of significant artifacts. Ceramics and decorative mosaic floors gave compelling testimony to the wealth and power this homeowner had possessed.

Years passed when archaeologists thought that the site had been searched and scraped of all noteworthiness. Then in 2013, Marie-Pierre Rothé took the helm of the archaeological team and expanded the bounds of the dig. The widened margins allowed archaeologist Alain Genot, among others, to explore the edges of what is thought to be the public space of the massive home.

This led to Genot’s 2015 discovery of a vertical edge, butted against a floor, indicating a wall had once stood in this place.

Further survey would determine that the open space had a total of three walls measuring 1.2 meters tall by 4 meters long. All had been painted in Pompeian-style frescos, as had the floor. In this respect, the floor stood out from other floors of the period, which were typically decorated with mosaic tiles.

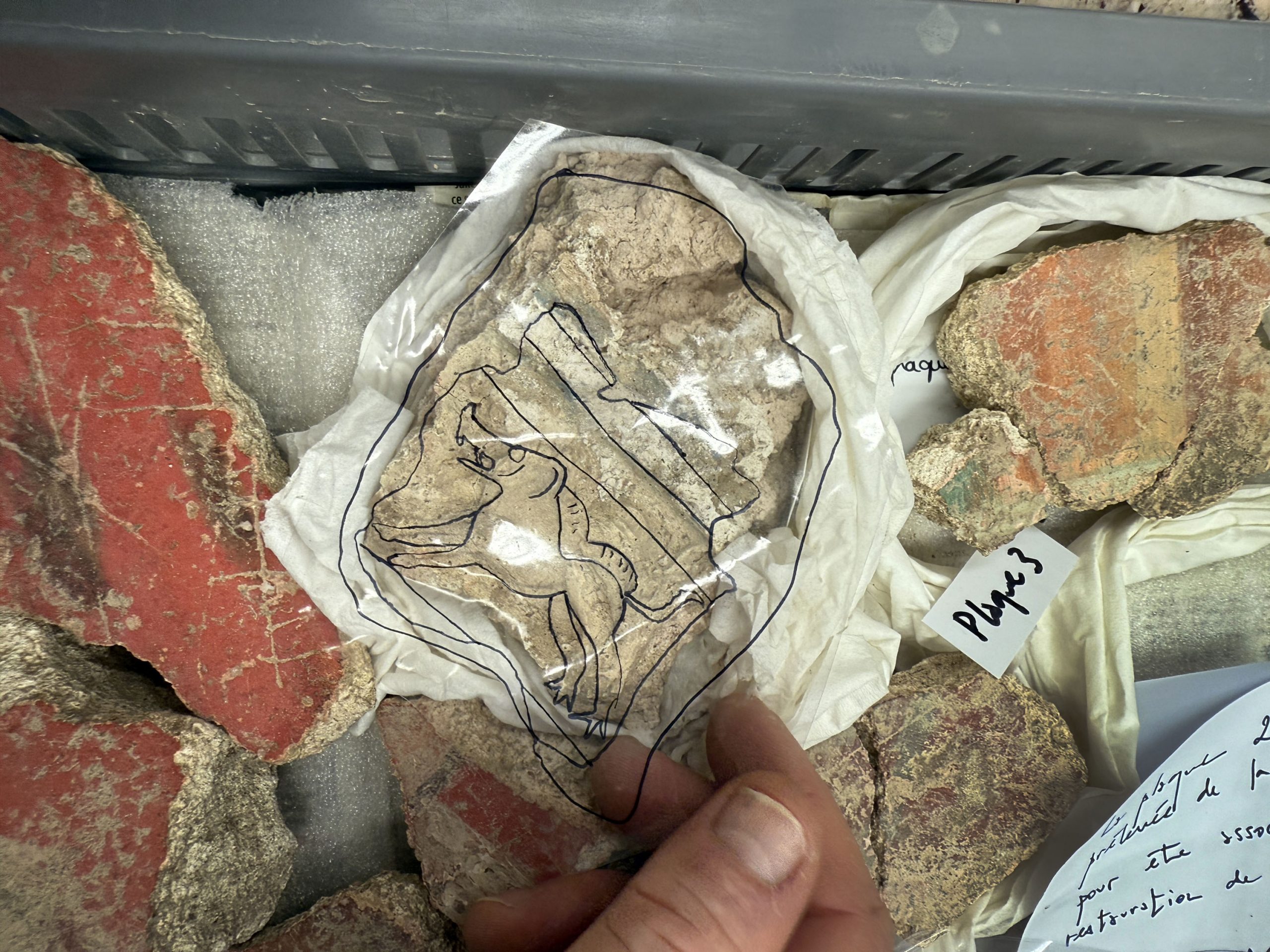

As more and more of the past returned to the surface, puzzle piecing quickly revealed the Harpist and other images that had been swallowed by the earth.

The Harpist’s image was once the focal point of the room’s left corner, with both a male and a female figure to keep her company.

These characters were interspersed with painted columns and cast against the most lush, luxurious, and expensive of Roman-era paints: cinnabar red. The painting of this fair model, her golden strings and her companions were meant to honor the gods while silently reminding the lower echelons of the homeowner’s affluence and influence, according to the researchers.

Finding the fresco was one thing; raising it was another. Breaks and damage to artifacts are an unavoidable consequence of bringing the ancient world to light. But to avoid unnecessary destruction, the extraction team strategically fractured it at points assessed as less integral to the find. When possible, naturally occurring cracks were used for removal points. “It’s a very huge work,” Genot said.

While working through the constraints of a time-consuming, labor-intensive, delicate extraction, Genot’s team came across an unexpected problem that demanded urgent resolution. Exposure to light causes the vibrant cinnabar red to deteriorate to colors that range from terra cotta to charcoal.

Further compounding this issue, the researchers could discern no rhyme or reason to how much light exposure would cause the decay in vibrancy. Some pieces changed immediately, while some could be exposed for months before a change was noticed. With each case specific and unique, archaeologists diagnosed site conditions, put protocols in place and amended them as necessary when circumstances changed.

They covered the work sites with canopies to block the sun’s rays. They carefully shielded the recovered pieces with canvas and plastics, coated larger pieces in removable adhesives, and reinforced them with wood and metal, not just to protect the integrity of their discoveries but also to support the weight of literal stone.

Fast forward 10 years down the road to summer 2025.

The Harpist now resides at the Museum of Ancient Arles and Provence, which itself was built atop the ruins of the ancient circus where chariot races and other feats of Roman spectacle were once held.

From behind a card-key access, gunmetal-color steel door labeled in French “Scientific Wing: Access Reserved for Authorized Persons,” Aurélie Martin emerges. Her copper-red hair, teal flowing blouse, white linen pants and inviting nature warm the cold, gray concrete corridor.

With Genot and his team’s Herculean feat of recovery complete, Martin and her colleagues have been charged with an equally tedious endeavor. It takes a “very specific team and space for this type of restoration,” she said. With this Marseille Province lab being home to one of only two publicly funded restoration workshops in all of France — and the short trip from the dig — it made perfect sense for the Harpist to find her home here.

Martin and her colleagues have spent the last 10 years sifting through and puzzle-piecing more than 600 cases with thousands of fragments, trying to figure out what is dirt, what is rubble, what is usable and what the image may have been.

They must do so knowing there are pieces that are missing and will never be recovered. They must also do so without bias or personal interpretation. And sometimes, after hundreds of hours invested, they must abandon a project because a consensus has been made by a panel of archaeologists, scientists, researchers and restorers that the general public would be unable to read the image without the researchers imposing their guesswork.

Aside from the challenge of reassembly without interpretation or bias, the restoration team is also facing elemental reactivity. “As early as the 1st century B.C., there is mention of the impact of light on paintings using cinnabar,” Rapilliard notes. “However, since not all frescoes with cinnabar blacken in the same way, this indicates that light is not the only factor at play in this alteration phenomenon.”

Even after being a heavy point of study in the archaeological and scientific community for the last 20 years, “the physicochemical reactions that take place in materials” are complex and have multiple factors that are still not fully understood, Rapilliard said.

Until a deeper understanding of cinnabar’s transformative properties is made, Rapilliard and Martin focus on a two-axis approach in preservation. The first is environmental control: the Harpist and others like her are delicately tucked away in storage controlled for climate, light and humidity until adequate preservation techniques and display spaces can be established.

The second is understanding cinnabar’s chemical composition (mercury sulfide, HgS) and the “chain of chemical reactions that take place” when it “is in the presence of chlorides (mineral salts),” Rapilliard said.

This deeper comprehension of the material, its composition and reactivity has led to recent advancements in desalination conservation and restoration. “We extract the chlorides and remove them as much as possible from the paint layer” to help prevent future color deterioration, Rapilliard said. This innovation could prove important wherever cinnebar paint is being preserved.

In the meantime, since the variables of color deterioration are still thought of as inconsistent, environmental control storage is currently the most effective preservation. However, this makes restoration difficult and viewing for the public almost impossible.

Now the team is inching closer to a long-term solution with the hope of publishing their findings within the next two years, and making the Harpist and her companions available for public view by 2029 for the first time in more than 2,000 years.

Katie Thornton served as interpreter for this story.