Once Urbino was a city with a university but in recent decades it has evolved into a university with a city. Now the last natives of this beautiful Renaissance town wonder what their future holds.

URBINO, Italy — Antonio Bisciari looks over this famous Renaissance city that has been his family’s home for 150 years and sees what the tourists see: a picture-perfect postcard town of unforgettable beauty. But he also sees something else.

“The people I grew up with are no longer here,” Antonio said. “So, staying in Urbino, a beautiful city, a marvelous city, but alone and with no friends is not worth it.”

“If you stay here for too long, Urbino becomes a jail; it’s not as good as one would think,” Antonio said.

To the thousands of tourists who flock to this scenic city each year, Urbino seems as lively and prosperous as it must have looked when the Duke of Urbino made it the hub of the art world in the 14th century. But beneath the facade of robust health lurks a different story.

According to city authorities, of the 5,000 people living inside the walls of this ancient town, 4,000 are now students. Although the exact figure isn’t known, some local experts, including University of Urbino professor Eduardo Fichera, estimate that the actual number of families living fulltime within the walls of Urbino is less than two dozen.

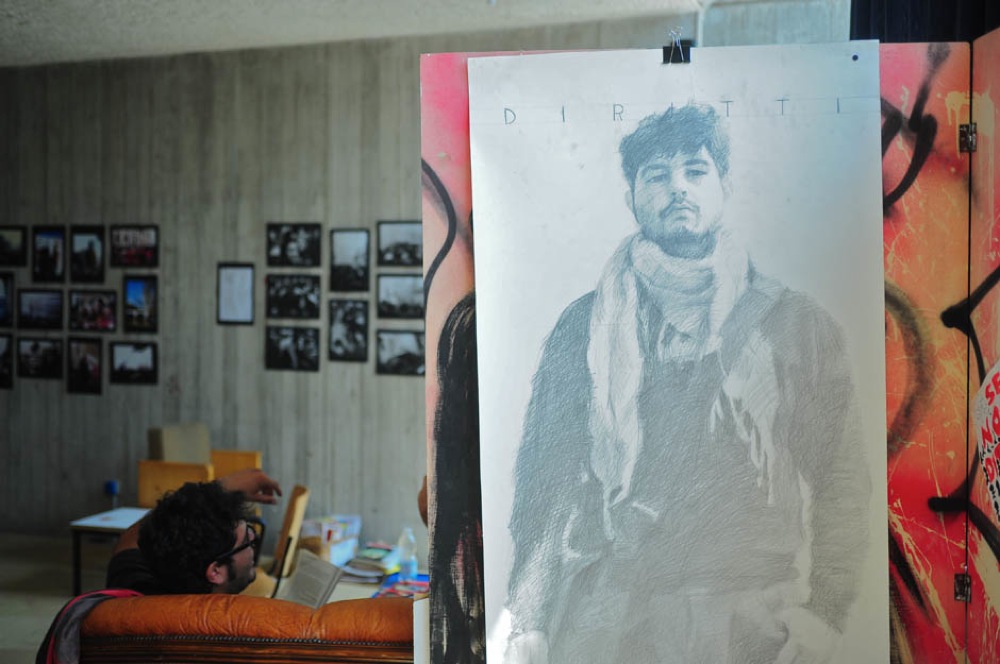

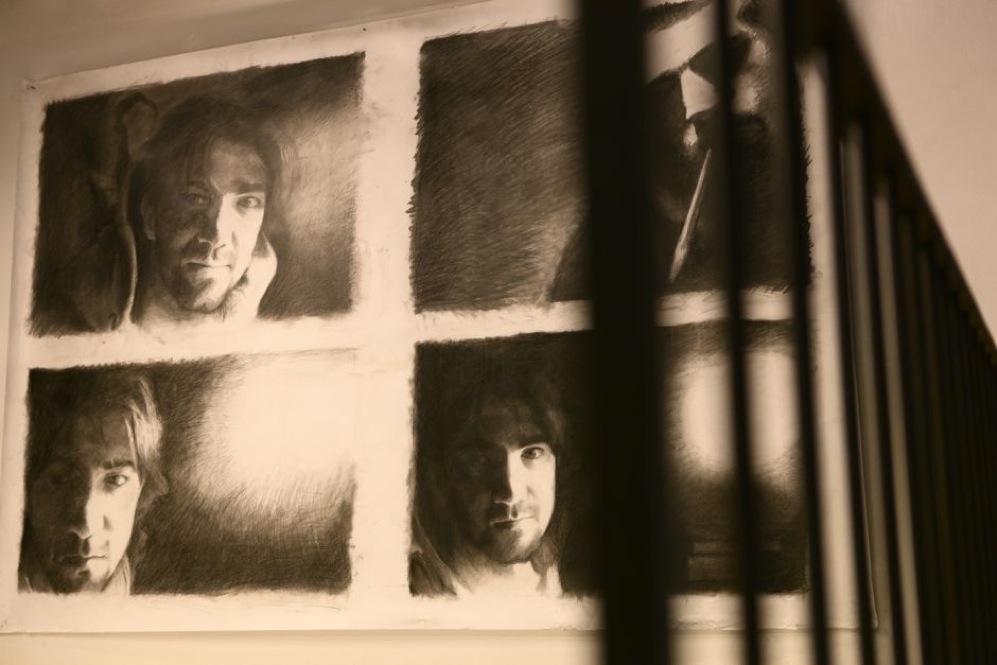

A reflection of the three generations of the Bisciari family, one of the last families of Urbino; Felice (grandfather), Antonio (son), and Paolo (grandson), enjoy each other’s company during a family dinner.

The Bisciaris are one of these last families. Felice Bisciari is Antonio’s father, and also the grandfather of Anna and Paolo. Though their family’s existence in Urbino dates back more than 150 years, the lingering question is, “How much longer will their ancestral name will be carried within this little city?”

The Stacciolis are another one of these remaining families of Urbino. Lamberto Staccioli, a life-long resident who raised his family in Urbino, is Giorgio Staccioli’s father, and two-year-old Eduardo Staccioli’s grandfather. He said he believes that “it is necessary to always remember where your family roots lie, and [he wants] to make sure [he] can give [his] family the feeling and sense of belonging with which [he] was also raised.”

Today the Stacciolis all live within the same fortress walls but the manner in which Eduardo is being raised is very different from his father’s. The atmosphere of the town has created a dramatic cultural shift.

It’s a town from fables, and when you’re 20 years old it’s perfect, it’s the right town, there are no dangers around and nothing bad ever happens. But when you are a grown-up man and you want to have a family it gets difficult.

Giorgio Staccioli grew up with nine of his closest friends. He left town to attend college, came back and opened his own bar, and built a family here in Urbino. But upon his return, eight of those ten families had moved on, leaving Giorgio and only one of his childhood friends to continue their lives together in their hometown. This trend had become prevalent, as Urbino transformed from a small city with a university to a university with a small city.

The younger generation of Urbino residents are conflicted on whether to stay within the historical walls they’ve grown to love or to leave in search of bigger opportunities elsewhere. They say that the choice is between different hurts: The feeling of missing your hometown, or the feeling of being alone in your hometown.

“You have to stay in Urbino on the 24th of December, the day before Christmas, when there are no students around, to notice how small Urbino is and how alone you really are,” says Antontello.

Carmen Staccioli, Girogio’s wife, is also struck with the same feeling around July each summer.

“Once the students have left this town becomes so empty. It becomes really sad and difficult to come to work,” she said.

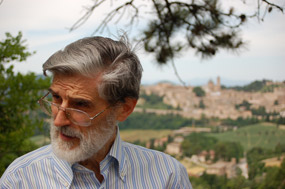

Lamberto, head of the Staccioli family, takes a moment to reminisce about the beautiful city of Urbino, a place where both he and his ancestors have called home.

Antonio believes Urbino is a beautiful and magical city, but that “it’s a town from fables, and when you’re 20 years old it’s perfect, it’s the right town, there are no dangers around and nothing bad ever happens. But when you are a grown-up man and you want to have a family it gets difficult.”

Those difficulties revolve around finding work, and places to live. The job market mostly has two options: working for the university, or running a shop. And real estate is expensive because student rents drive prices up.

So Antonio deals with a 90-minute daily commute to work. But he feels the commute is worth it, because he wants to raise his family here, close to their roots. However, the saddening feeling of seclusion still tears him.

“Living within the walls of the city is expensive and Urbino doesn’t offer a lot of work,” Carmen Staccioli said. “The opportunities are very limited.”

Though she only moved here a short seven years ago, she claims it is still evident to see the distinct evolution that the city has experienced through this brief window of time.

This evolution has been especially evident to the older generations.

“The way of living is really different now,” Felice Staccioli said “Fate allowed the exterior part to remain as it was, luckily, but the relationships between people have really changed. Now everyone just ‘harvests their own fields’ and there is more individualism; in the past there was much more solidarity and brotherhood.”

In Lamberto and Felice’s youth, the streets resonated with the laughter of children and piazzas were places where families and friends gathered. But now, the sounds of partying students drinking from open beer and wine bottles echoes down the narrow cobblestone streets from early afternoon until three in the morning, making it hard for children and residents to sleep.

But while the last residents of Urbino see the students changing the quality of the life they cherish, they also know that their livelihoods and futures are tied to these same students.

“The youth help boost the town’s economy because they are constantly buying drinks, shopping, and keeping the town alive,” Lamberto said.

Antonio’s brother’s family has already moved away to Bolzano, leaving Anna and Paolo as the only future Bisciari descendants within Urbino.

“I belong to a generation that just wants to move away and look for something out of these walls,” said 17-year-old Anna.

She and her brother are torn with the tough decision of whether to raise their own families here, or search for better opportunities. Though it would make their family happy to see them stay and continue their legacy within the walls of this extraordinary city, they would rather see their children choose for themselves.

Antonio said he feels, “I can only help them to choose, but it’s their call. I’d like them to stay here and have children here; I’d be happy. But it’s their happiness, not mine.”

Slideshow

Click on Image to Show in Lightbox.