A heart-shaped book holds music, poems, a journal—

and a 500-year-old mystery

The sign reads “Oliveriana Biblioteca.” Step by step, with a long line of stairs in front of us, we make our way into the hall of the ancient library in the center of modern Pesaro, Italy. As we look around, all we can see are books of various shapes and sizes behind glass doors that seem to scream, “Do not touch”.

The librarian, Maria Grazia Alberini, greets us with a smile as my interpreter explains who we are. She walks into a back room and returns a few minutes later. In her hands she holds the mysterious book.

“Here,” says the librarian as she passes it to me. “Hold it.”

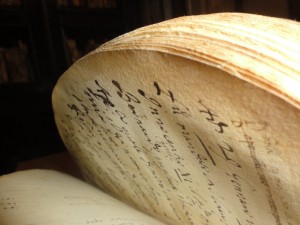

In awe, I take the book. I slide the latch, creating the sound of an age-old story unfolding. Dust fills the air as the leather cover opens into the shape of a heart. My finger moves over the dry pages. They are more than five centuries old.

“It was found in this library,” says Alberini. “We asked Mr. Vincenzo Santoro to restore it—because he is the best.”

It was a week earlier in Santoro’s shop that I first heard about this unique book, and decided I had to see it, hold it, and feel its mystery. In the closet-sized workspace in Urbino, Santoro greeted me excitedly with outstretched arms, calling “Ciao! Ciao!” and looking as if he were welcoming a celebrity or an old friend. His wide eyes glistened through tiny glasses; his scruffy beard complemented his thick black hair with gray highlights. The five-foot-tall restoration expert seemed twice that height with his joyful presence.

The walls were covered with his successes, pictures of antique but now renewed books and paintings were framed and hung with pride. Santoro said that he started studying the art of restoration during high school and continued during college at the University of Urbino. He decided he wanted to teach the technique to younger students. Now a high school teacher in the city of Urbino, he runs a well-respected sideline in restoring books and works of art from all around Italy.

Books, he said, were his favorite. One in particular caught my attention as he explained that it was one of the most mysterious objects he had ever seen.

“J’ay Pris Amour,” he called it. Translated from old French, the title means “I have taken love.” He pointed to a picture on the wall. There it was—a book in the shape of a heart.

He said that the book had three parts: a section of written music, pages of poems, and a journal. “The author is unknown,” he added. “Based on the restoration process, I know that it was written in the 1500s. I think it might have belonged to Duke Guidobaldo’s wife, Elisabetta Gonzaga.”

Now, 20 miles from Urbino, I stand in Pesaro’s Oliveriana library with the open heart sitting in my hands. I see the words in front of me as I look at the first few pages of the book: “J’ay Pris Amour.” The words on these pages are the lyrics of a French chanson popular in the 1400s. The written music is the accompaniment that was to be played on the lute. I start to wonder about Santoro’s speculation: Might this book really have belonged to Elisabetta Gonzaga?

[pullquote] Might this book really have belonged to Elisabetta Gonzaga?[/pullquote]

I can almost see her, the weight of Urbino on her shoulders, furthered burdened by worries of her husband’s health. As heir of the great Duke Federico da Montefeltro, Guidobaldo needs to keep the city of Urbino running prosperously and peacefully, but his body has failed him. I imagine her sitting on a chair next to his bed, managing interruptions from members of court and governmental subordinates who come to her with personal concerns, requests to consider, and legal matters to decide. Seeing the stress in her eyes, Guidobaldo thanks her for never leaving his side.

She smiles and gives a tiny giggle as if to say that even the thought of leaving him is absurd. She might then pick up her lute. Holding the neck of the instrument with one hand, she places the other ready to pluck the strings on its round, wooden frame. Then she reaches for her book, opens it to form the shape of a heart, and sings in a sweet, gentle voice, “I have taken love as my device…”

I flip past the pages holding the music of “J’ay Pris Amour” to reach the second part of the book, this one containing words just as deep: hand-written love poems. My imagination stirs again as I wonder whether this might be Elisabetta’s work—or do I see someone else now holding the book?

I envision a woman grasping an ancient pen, dipping it into the black liquid that sits in front of her, and then opening the heart and starting to write. The pen bleeds these words onto the paper… “Chi dice chio mi do poche pensiere” (Who says that I give to myself few thoughts.) She continues to write as she thinks of the man to whom she will present this unusual gift. “Alzare il capo e dir qual cosa fia” (To lift the head and to say that something will do.)

The last section of the book served as the diary of a wealthy family in San Lorenzo in Campo. (photo by Mikayla Francese)

I reach the last part of the manuscript, the section with the most clues to its history. Ink faintly shows the name Tempesta Blondi. Experts have identified him as a successful landowner who lived in San Lorenzo in Campo in the 1500s. Around the edges of the tarnished pages are notes describing Blondi’s his marriage as well as the death of his father. The title on the fly-leaf of the book reads “Miscellanea di Tempesta Blondi,” confirming that this final section served as a sort of diary.

Blondi was a wealthy man whose life was full of culture. He and other members of his family were patrons of and participants in the arts, particularly music and poetry. Looking over the diary, it’s easy for me to imagine a peaceful night in the life of the Blondis.

The gentle sounds of the lute fill the household; perhaps a few children dance to the beat. Outside, white flakes fall from the sky; inside, candles bathe the family in a warm light. Tempesta sits on the cushion of a love seat; his wife sits across from him knitting a child’s winter hat. He plucks the strings of the musical instrument that has shaped his past as it continues to bring joy to his present. His oldest comes into the room carrying the book. Tempesta takes the heart and writes out a few sentences to document the evening’s events, while planning on many more to come.

As I close the book and study its cover of dry, broken leather, I am pulled back into the present. It was just a couple of days ago that I asked Santoro to describe the process of how he restored such a delicate piece. He explained that long journey while demonstrating some of the techniques on a more recent restoration.

“Very carefully,” he said as he slowly took apart the sewn binding one strand at a time, and then removed the pages from the string. “I must scrape off the insect residue,” he explained as he cleaned each page—380 in all. Santoro wiped Gomma, a dry rubber powder, onto each sheaf and placed the newly fluffed paper into water. He removed the paper to then rub a thick, clear glue onto the soft pages—cautiously so as not to rip them. He opened a drawer in front of him. “My specially imported Japanese paper,” he said as he placed a piece on the table. He sandwiched each newly hardened page between the paper and a piece of gauze and waited for it to dry…

I hand the book back to the librarian and contemplate its history, the facts and the imagined possibilities. It is certain that Tempesta Blondi was the author of the journal that appears on its later pages. But who created the book? Who owned it and who wrote the music and poetry onto its pages before the book came into the possession of the Blondi family halfway through the 16th Century? At first, I found it too hard to accept how much is unknown. Now I realize that this is part of its beauty, and a measure of Santoro’s skill. This ancient book is still full of life, love, and mystery—and that is what makes it precious.

This article is from Urbino Now magazine’s Arte e Cultura section, which reports on the arts and culture of Urbino and the Le Marche region. Please view more magazine articles or order a complete printed copy of Urbino Now.