Story by Thomas Murphy, Lydia Perez and Mariko Rath

Photos by Thomas Murphy

As in most years, the streets of Arles came alive on June 21 for La Fête de la Musique, France’s annual midsummer night music festival. But in La Roquette, a neighborhood in the midst of change, one musical group took the opportunity to make a political statement.

In Place Genive, one of the historic neighborhood’s cozy gathering spots, a choral group known as La CLASH Chorale de Chants de Lutte Arlésienne, sang “Gentrifica” by longtime Arles resident Henri Maquet. Beginning with the chant “Airbnb. Airbnb. Airbnb, Airbnb, Airbnb” to the tune of the theme song from the ’60s TV show “The Addams Family,” they sang in the Provençal dialect:

“D’uno meno tranquilo

veiràs la disparicien

di bravis arlaten.”

“In a quiet way

you will see the disappearance

of the brave Arlesians.”

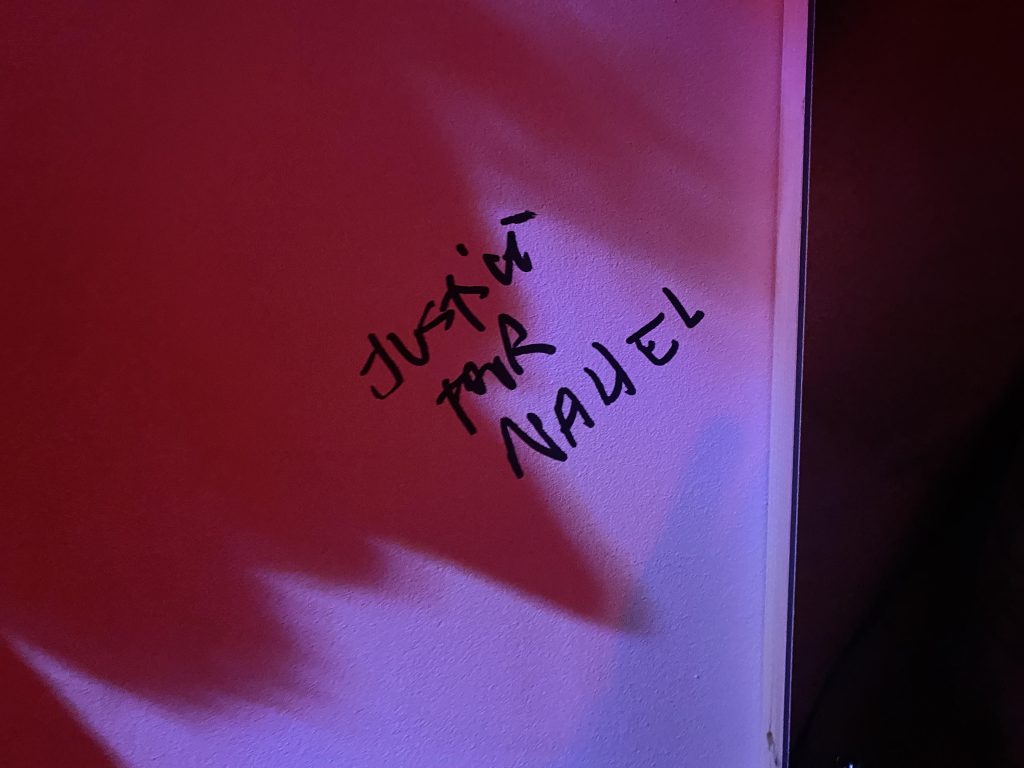

For La Clash, the festival was a chance to shed light on the impacts of gentrification, which is pushing some Arlesians out of the city’s center and changing life for those who remain.

Some residents of Arles believe the city’s rising tourism has become a burden for longtime residents, especially those in La Roquette, the city’s oldest neighborhood and the home of immigrant communities.

Arles is renowned for its rich history and vibrant culture; as such, it has long attracted tourists. But, in recent years, with new attractions and new ways for people to capitalize on the city’s charm, some say Arles is losing what makes it special.

Exploring this vibrant area as a tourist in summer, it’s easy to be dazzled by the city’s charming winding alleyways and impressive monuments. The architecture of the distant past is well preserved and the streets are alive, filled with people eating at restaurants or looking through shops and galleries. What you may not notice are the scores of Master Lock key safes, the “for sale” signs hanging in windows, or the silence that falls in winter after the tourists have gone home.

“It’s changing. There are less people now, it’s rather difficult,” said Jean-Marc Bernard, a retired mason devoted to the preservation and improvement of his hometown. Having lived and worked in Arles his entire life, he knows its history well and explained how his hometown became “…a holiday village, only for tourists.”

Bernard explained that Arles’ factories were closed prior to 2003 when many buildings were damaged by major flooding from the Rhône.

With one of its main revenue sources gone, the city decided to invest in its major industry, tourism.

With an already impressive arts scene, featuring the Les Rencontres d’Arles photo festival and the legacy of Vincent Van Gogh, it made sense to find ways to draw more visitors.

In June 2021, the LUMA Tower opened, adding another tourist attraction to Arles. Spearheaded by pharmaceutical company heiress Maja Hoffmann and designed by the architect Frank Gehry, the gleaming structure has solidified Arles as a destination for the arts.

Gertie, a resident of La Roquette for 10 years who didn’t want her full name used, said that the addition of art spaces like LUMA meant that ”Arles became attractive. Arles was the place to be.”

The rise of tourism has driven some property owners to capitalize on the market by listing with short-term rental services. Companies like Airbnb have made it easy for hosts to earn a lot of money renting their homes.

“There was a lot of tourists, so there was a lot of Airbnbs,” Bernard said. “People were very interested to gain money.”

“Aqui soun li touriste,

que pagon li mai riche que compran nostis oustau,

per faire mai de sòu.”

“Here there are tourists,

who pay the richest.

Who buy our houses,

to make more money.”

According to AirDNA, which tracks vacation rental data, there are 220 short-term rentals listed in La Roquette, which had fewer than 2,500 inhabitants in 2006, according to the city’s website.

Data recorded by Insee shows the number of secondary residences in Arles, which increased from 588 in 1999 to 1,693 in 2021. Karine Bernard, Jean-Marc’s wife, explained that “Parisians or foreigners…buy these houses, not even to make them Airbnbs or apartments. They’re empty for most of the year and just a second house for them.”

Some investors leave homes empty, waiting for their value to increase to sell later after the price increases. Insee data shows the number of vacant accommodations rose from 1,632 in 1999 to 3,521 in 2021, growing by 1,378 after 2015. Bernard reported that he bought his home for 85 euros per square meter when he moved to La Roquette 30 years ago. “Now,” he said, “it is worth about 3,500 (per square meter.”

“T’an vendu e per cent e per milo.”

“They sold you for a hundred and a thousand.”

As prices have risen, many longtime residents of La Roquette have left the neighborhood. ”The houses are so expensive, so you can sell them for a lot of money,” Bernard said. “Somebody can sell their house and buy a very comfortable villa with a garden.”

This exodus, combined with the growing number of short-term rentals and empty investment homes, have caused the loss of La Roquette’s spirit, some residents say.

“Before, the neighborhood was a real melting pot; there were several kinds of people,” said Gertie. Now, the neighborhood is becoming less diverse, with tourists sometimes outnumbering locals strolling through the district’s winding streets.

“Mass tourism can kill the spirit of a city,” said Thomas Corolleur, the former president of a community space in the town center called Parade. “[Visitors] want to find a place that has spirit, but if you have too many tourists you kill the spirit.”

When asked what he thought a solution would be, Corolleur said, “It’s a question of balance, how to find the right balance between people coming from outside and people living here full time. It has to be fine-tuned.” He spoke of other cities like Barcelona that plan on banning Airbnb by the end of 2028, and how this movement is a good thing for residents.

Vanille, who has lived in La Roquette since 2014 and did not want her full name used, explained that the best course would be to move away from a profit-centric model of home sharing. She’d prefer to see people use systems like Home Exchange, where members can swap homes or host to earn points, not cash.

”The big problem ,” she said, “is that there’s a lot of Airbnbs that are just Airbnbs, they’re not houses that you put on Airbnb for a week when you’re gone.”

Like many cities in France, Arles relies on tourism. It will always be rich in art and culture, but the influx of short-term rentals to tourists allows the sense of community in the heart of the city to slowly deteriorate. Just like any other story of gentrification, money prevails, pushing out long-time residents of La Roquette, and making room for the wealthy.

“Nautri, pauris arlaten

Sarem pas pus aqui

Nous mancara d’argent

Per resta au pais.”

“We other poor Arlesians

We won’t be here anymore

We will be short of money

To stay in the country.”

Listen to Henri Maquet sing “Gentrifica.”