By Ella Slade

I point to my dinner, a full plate of tomato salad and fried egg crêpes, and rack my brain for the French translation of “this looks good.” The words exist only in English, and I stifle a sentence I know my host won’t understand.

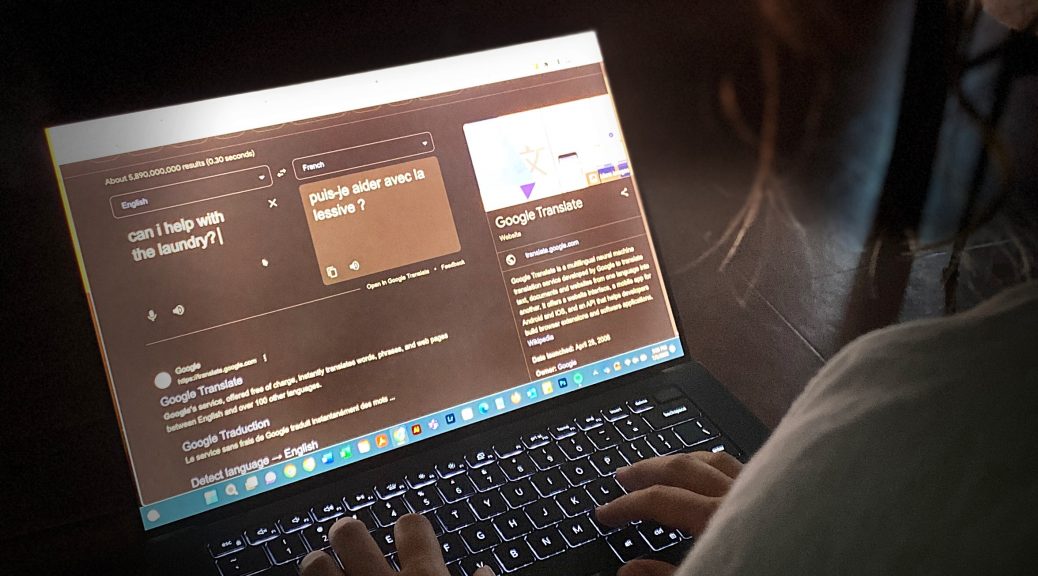

Communication with my host “mom,” a wonderful woman named Djamila, involves an amalgamation of French (with the aid of Google Translate), English, gestures and facial expressions. I have never before experienced this kind of difficulty in finding the correct words; English was always my strong suit, and I have nearly three years of communication-related college courses under my belt.

When it comes to speaking French, however, the average second-grade student could shamelessly wipe the floor with my written and verbal abilities. I now feel slightly ignorant in calling myself an expert communicator, as I’d only ever attributed the skill to communication in my native language.

The frustration I feel at not being able to exactly express my thoughts is a new and special experience. If I could tell Djamila anything, I’d ask her where she found each and every one of the paintings that ornament her apartment walls. I’d speak precisely about the differences between my town in Iowa and Arles, France. Instead, I use choppy French to say something about how Iowa has a lot of farmland, a lot of corn, as she nods and smiles.

Surprisingly, I continually find that being “taken down a notch” in my preferred area of expertise is not discouraging. As my proficiencies are challenged, I gain new skills.

After one of Djamila’s home-cooked meals, I now can express my satiety in French, thanks to her teaching. We laugh together without use of complete sentences, and respond to the television with sighs and smiles and eye-rolls.

This is a personal reflection and does not necessarily express the opinion of The Arles Project or program sponsors ieiMedia or Arles à la carte.