“One Love” hidden in the hills of Renaissance Italy

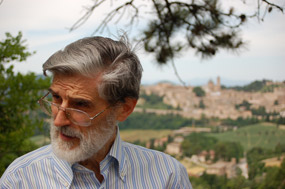

URBINO, Italy – Alessandro Fusco is leaning over a railing surrounded by lavender flowers and clay-tile rooftops when he suddenly jumps, waving his arms in excitement.

Wow! Take the picture. . . Come, come, come. A humming bird… please, please you see it? Stay here, it’s there. Phew! That was great!

Fusco, 22, is about as unconventional as a Jamaican bobsled team.

Born and raised on the Italian Island of Sardinia, Fusco is a full-fledged Rastafarian, a follower of the faith and lifestyle borne of the anti-colonialism, poverty, spiritualism and marijuana of post-war Jamaica, a Caribbean island he has never seen.

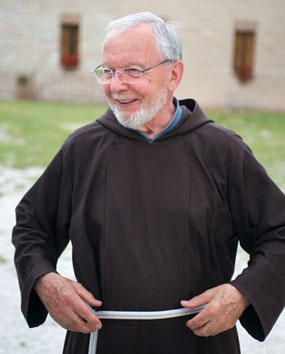

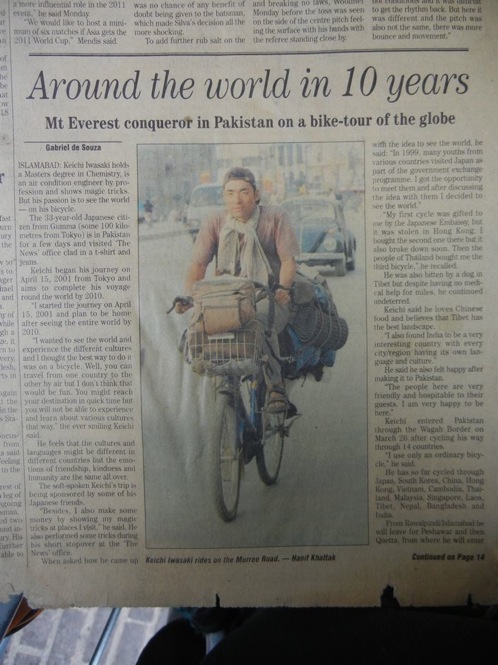

Marco Mollona and Alessandro Fusco meeting for the first time.

His dark brown hair is woven into long thick dreadlocks. He has his own reggae album entitled “Prisoner in Babylon” under his stage-name, ShakaRoot. He speaks English in a Jamaican accent, having learned the language listening to Bob Marley and other English-speaking reggae artists.

He pronounces the word thing as “ting.”

Fusco is also a sociology student at the University of Urbino. During his off-time he enjoys being out in the rolling hills and sleeping under trees, despite having the option of a roof over his head. He appreciates nature so much he will at times stop in mid-conversation to acknowledge the presence of a scenic landscape, a humming bird or an interestingly coloured insect.

Respecting Mother Nature is an important value in the Rastafarian movement.

“Rasta is all about respect,” he says. “Water is a holy ting, a natural flow you have to respect. You have to give thanks to the water, to the air you breathe.”

Rastafarian faith is Fusco’s way of life despite being raised and now surrounded by Italy’s Roman Catholic traditions. Fusco says people need to choose their own roads, follow their own paths and the Rasta life, no matter how odd it may seem here in Urbino, is his path.

Fusco is not the typical Italian. But he isn’t the typical Rastafarian either.

You become a Rasta in your own way, not in another way.

“You become a Rasta in your own way, not in another way,” he says. “So every Rasta man is different, unique in this world because he has his own spirituality.”

Fusco is not ethnically African even though the Rastafarian faith was originally founded by blacks who were in the fight for freedom from white oppressors.

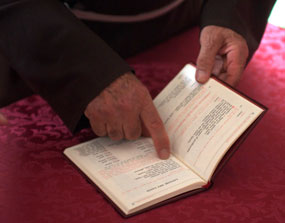

He says he also abstains from any kind of marijuana use. Some Rastafarians believe that marijuana grew on the tomb of King Solomon and that it is useful during prayer.

In 2008, The Italian Supreme Court ruled in one case that it was not a criminal offence but a religious act when a Rastafarian smokes or possesses marijuana, but since then there has been no similar court rulings and marijuana-use remains a crime in Italy.

There is a special irony to an Italian youth or any Italian embracing Rastafari.

During the 1930s, the same time period the Rastafari faith originated, Italian fascist dictator Benito Mussolini invaded Ethiopia, which is considered the sacred Promised Land among Rastafarians.

Italian Rastafarian communities, predominantly in southern regions like Sicily, did not begin to emerge until the 1980s.

“So the relation between Italy and Rastafari is that you put yourself against the brutality made by the fascist people,” Fusco says. “I was born in a place that Mussolini created, so I put myself against those actions, even though those actions in a certain way created me.”

Iyared Mihirete Sellassie is the first vice-president of the Federation of Rastafari Assemblies in Italy (F.A.R.I), an organization that was created in efforts to centralize and organize the movement. Iyared is seen by many of the younger Italian Rastafarians as a spiritual leader or older brother in the faith.

Iyared writes, “It is [a] heavy and proud task to bring the word of Rastafari to this land, where [early Christian] fathers suffered martyrdom and persecution in the very early days of Christianity.”

In Urbino, the Rastafarians are relatively few, and not a cohesive group. They are not even acquainted with each other, for the most part.

Marco Mollona, 23, is also a Rastafarian and a language major at the local university. Until recently, he had never heard of Fusco.

Alessandro Fusco and his friend Rocco Salerno preparing for a jam session with the hills behind them.

On an overcast day, while walking down a narrow cobblestone street, Fusco turned and instantly recognized Mollona as a fellow Rasta. They introduced themselves, and then both whipped out their cell phones to exchange phone numbers and Facebook information.

The two Italian Rastafarians then parted ways. Finally, after three years of studying in the medieval city, Fusco had another Rasta friend.

Meeting Rastafarians is not a top priority for Fusco, who says he has no prejudice and smiles with just about everyone he meets.

“The message of One Love: we are all one. If you speak to a baby, an old man, it’s the same message,” he says.

***

Mollona, who was brought up the traditional way, found the Rastafarian faith two years ago. He says at first some people were not sure how to accept his new lifestyle, but eventually they came around. His mother complains only about his dreadlocks, although she has been getting used to the look.

Fusco has a very close relationship with his mother — “great love from mama,” he says. She tells him he is “free to find spiritual divinity in all things.”

Fusco and Mollona listened to reggae, among other genres, at a young age and eventually began to soul-search and think deeply about their lives.

“The first time you hear Bob Marley you get shocked by his music,” Fusco says. “When I first heard ‘Redemption Song,’ it gave me a great emotion inside of me; it was like I was crying. I fell in love with life in that time.”

Fusco also says he sees a lot of strong ties between Marley and his late father, both victims of cancer. He says Marley is a father-figure.

***

The field of the Fortezza Albornoz Park is packed and the sky is dark. Fusco swivels through the dense smoke-filled crowd of laughing, singing and swaying students. The Sound of Sun, a female-fronted reggae band, is already on stage, meaning Fusco is late. He hops over a fence and finds himself backstage, runs up the stairs and joins the band in the most fluid, discreet fashion.

After a few more cover songs, Fusco is centre stage as his performance persona, ShakaRoot the crowd erupts in cheers as he belts out his own original reggae songs.

Fusco’s decision to follow the Rastafarian faith has been a long evolving process.

“So I was 11, and it was gradual. First I listened to the songs, the songs gave me a lot of emotions, so step by step I heard Peter Tosh. Peter Tosh just taught me a lot of tings about Rastafari in his music and gradually I became a Rasta,” he says. “You open your heart to Rastafari.”

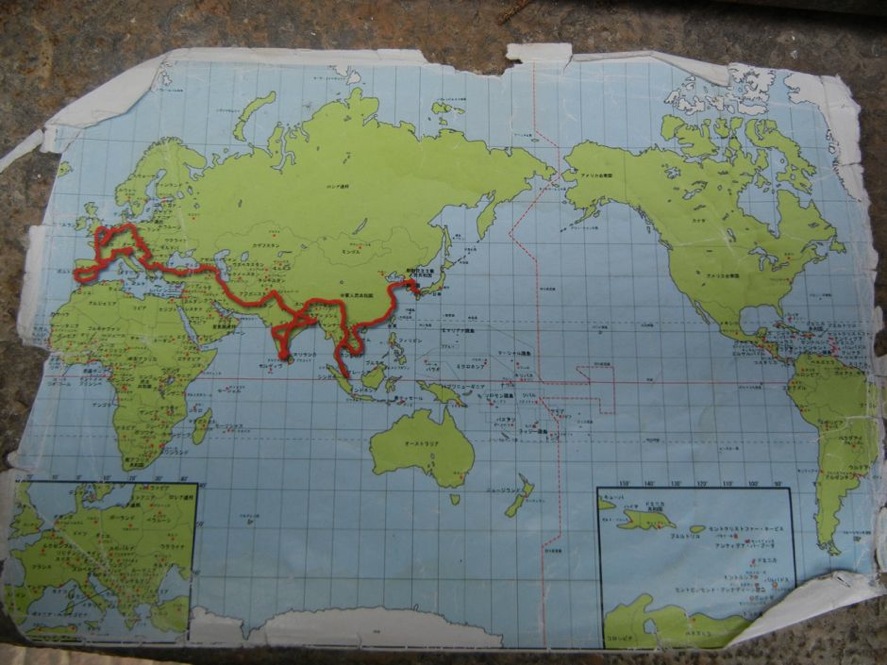

Something Fusco is the most passionate about besides his faith, music and nature, is children. After he graduates from University in February 2012 he plans to travel to South Africa where he will teach guitar and Italian to the local kids.

“Identity is the most important thing. That is what I want to bring with my music, starting from children because every child in this world is different from the other.”

Fusco believes children and youth are the cornerstones of the world, paying reference to Bob Marley’s song “Cornerstone.”

“They say that the stone the builder refuses will always be the head cornerstone. To me every youth is the head cornerstone of the future,” Fusco says. “So, what we need is to open the doors to creativity. Like one song of mine says, ‘life is mine, like sunrise, let me shine, you give to me wings and shine, I wanna rejoice, let me fly’ so that’s my message y’know?”

Chef Nicola Costantini cleans his cooking space before beginning to prep his meal. He started to cook his meal early in the morning.

Chef Nicola Costantini cleans his cooking space before beginning to prep his meal. He started to cook his meal early in the morning. In order to prepare the third course, the dessert course, for his dinner he places cooked peaches into dishes. The peaches were cooked in a pan with a wine sauce.

In order to prepare the third course, the dessert course, for his dinner he places cooked peaches into dishes. The peaches were cooked in a pan with a wine sauce. Fresh pastry dough was used to make the crust of his peach tart. He cut it up into sections and rolled it out before placing it on the peaches.

Fresh pastry dough was used to make the crust of his peach tart. He cut it up into sections and rolled it out before placing it on the peaches. After cooking the dessert, it is removed from the pan and flipped upside down. A swift aroma of freshly cooked peaches filled the room as the plates were uncovered.

After cooking the dessert, it is removed from the pan and flipped upside down. A swift aroma of freshly cooked peaches filled the room as the plates were uncovered. The veal was seared in a pan and then braised in the oven. The pieces of veal were placed on racks before being put into the oven to braise.

The veal was seared in a pan and then braised in the oven. The pieces of veal were placed on racks before being put into the oven to braise. In order to get the most flavor from the ginger root, he grated it, and then later squeezed the juice from it. Ginger was one of the most prominently used spices in the Renaissance era.

In order to get the most flavor from the ginger root, he grated it, and then later squeezed the juice from it. Ginger was one of the most prominently used spices in the Renaissance era. Colors and seasonings are a big thing in the kitchen. Everything was seasoned in a way that complemented the other elements on the dish. This was the same way things were done in the Renaissance.

Colors and seasonings are a big thing in the kitchen. Everything was seasoned in a way that complemented the other elements on the dish. This was the same way things were done in the Renaissance. Fresh vegetables and fruits were common in Renaissance cuisine. I Calanchi agriturismo uses fresh vegetables from their garden.

Fresh vegetables and fruits were common in Renaissance cuisine. I Calanchi agriturismo uses fresh vegetables from their garden. Fresh herbs are some of the best ways to season things. Fresh herbs were common in Renaissance cooking, not always for seasoning, but also as decoration.

Fresh herbs are some of the best ways to season things. Fresh herbs were common in Renaissance cooking, not always for seasoning, but also as decoration. Having the same seasonings and taste as there was during the Renaissance. There was a harmony of spices and fruit flavors.

Having the same seasonings and taste as there was during the Renaissance. There was a harmony of spices and fruit flavors. The finished products resembled Renaissance cooking, but in a modern style. All of the flavors are still present, the looks and techniques; however, are not the same.

The finished products resembled Renaissance cooking, but in a modern style. All of the flavors are still present, the looks and techniques; however, are not the same. Before prepping for service, Chef Costantini mentally prepares for the night ahead.

Before prepping for service, Chef Costantini mentally prepares for the night ahead.