The Return of the Illustrious 28 - Urbino Project 2015

For a few special months, the portraits that inspired Duke Federico have been back in Urbino.

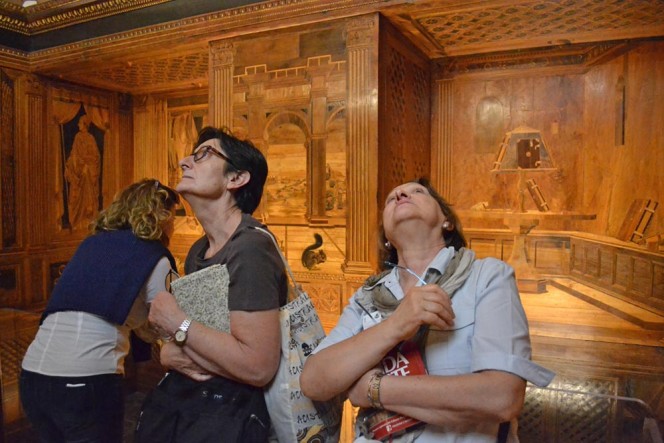

URBINO, Italy - The room is small and square and smells of wood. From the floor to just above the heads of spectators, intricate inlaid patterns cover all four walls. Giving the illusion of three dimensions, the detailed marquetry depicts suits of armor spilling from closets, books stacked on shelves, open cabinet doors revealing musical instruments, and swords appearing to lean against the walls. But lately, all eyes have been drawn upwards, past these carved scenes to 28 large rectangular portraits that fill the top half of every wall. The subjects gaze down, each an important man from the past, ranging from philosophers, to writers, to Popes.

The portraits, coupled with the inlaid images, give an insight into the mind of the room’s creator, the former duke of Urbino, Federico da Montefeltro. Federico chose these men to adorn his studiolo, his cherished private study, because they epitomized the ideas he valued. The portraits hung proudly on the study’s walls until the last duke of Urbino died in the 1630s. They were then taken from the palace; 14 were later returned, leaving the room—and its representation of Federico’s guiding principles—incomplete.

The detailed woodwork that lines the walls of the Studiolo were designed by Florentine artists and then carved by students in an apprenticeship.

Now, for the first time in 400 years and thanks to the cooperation of the Louvre in Paris, the study can be seen in its entirety. All 28 “Uomini Illustri,” or Illustrious Men, have been hanging proudly on the walls since March and will continue on display until early July. According to Cecilia Prete, professor of modern art history and museology at the University of Urbino, few studies exist today like this, one that can be seen almost exactly as it was when first built and used by Federico.

Federico was a true Renaissance man. He was a dedicated scholar, a fierce warrior, and an admirer and supporter of the arts. He commissioned the Palazzo Ducale, home to the famous study, to be built in the 1450s. He hired architects Bartolomeo, Laurana, and Giorgio Martini with intentions of bringing new life to the city. Federico began construction on the studiolo in 1476. It would become one of the most famous studies in the Marche region because of its meaning, detail, and cultural value.

Bonita Cleri, researcher and professor of art of the le Marche region at the University of Urbino, explained that the restoration of the studiolo, with all 28 paintings, looks almost identical to the way it did during the reign of Montefeltro. When paintings are absent from the studiolo, they are replaced with monochrome prints, which are far less impressive than the originals.

The duke built this study as a place to be alone and spend time devoted to his soul. According to Cleri, it was not a place to go to read and write, but to think, meditate, and be inspired. His inspiration was drawn from the illustrious men that hovered above him. Like teenagers choose posters of people and places that speak to them, Federico chose his illustrious men for values he admired.

The exhibit, which only lasts from March 12th to July 4th, gives tourists only a few months to visit the study completed.

Originally, each portrait was accompanied by a description carved beneath it, said Prete. Federico chose Augustine “for his sublime doctrine and for his luminous search for celestial words,” Moses “for saving the people and providing them with divine laws,” Pope Pius II “because he increased his realms by war and adorned it with the marks of eloquence.” Dante was included “on account of the verses he produced and the poetry he wrote for the people with diverse learning” and Aristotle “for the philosophy handed down in the proper and exact manner.”

After making his fortune as a condottieri, a warlord, Federico took to the arts. According to Cleri, the study was meant to represent the classical, humanistic concept of Otium—leisurely contemplation. It was also a place he could use to demonstrate his values, culture, passions, and accomplishments to the outside world. At the time, Federico favored Flemish painting techniques over the Italian style because their use of oil on wood gave paintings a glossy look. The duke commissioned Giusto di Gand from Flanders to create the portraits of 28 men who inspired him.

In 1631, after the last duke Francesco Della Rovere died, authority over the region was transferred to the Church. The pope sent his nephew, Cardinal Antonio Barberini to Urbino to take power. He ended up taking much more. Barberini cut out of the walls the 28 paintings in the studiolo and sent them to his palace in Rome, where they stayed for most of the 18th century. After a family quarrel over inheritance, the 28 paintings were split up.

Fourteen of the portraits stayed in the home of Barberini until a decree allowed them to be released by the public and sold on the market. They were eventually found and bought by the Italian state, which sent them back to the National Gallery of Le Marche, which is housed within Urbino’s Palazzo Ducale. The other 14 were bought by a wealthy family and traveled through the hands of a banker, a pawnbroker, and finally Napoleon III, who entrusted his collection to the Louvre. Fortunately, National Gallery Superintendent Maria Rosaria Valazzi, had spent time studying at the Louvre and even worked as an intern there. In part through her connections, the 14 portraits in the Louvre were recently returned to Urbino—temporarily—in order to re-create the studiolo in its entirety.

For the residents of Urbino, this event is special because they have regained a missing piece of their past. To Prete, the study is a mirror of Federico, a mirror that has now been fully reconstructed. She describes the return of the 28 illustrious men, even if only for four months, as “a victory.”