Carved in Stone - Urbino Project 2015

- Rachel Mendelson

- On June 23, 2015

The last sandstone sculptor in Sant’Ippolito keeps her city’s ancient traditions alive

Natalia Gasparucci is strolling the quiet streets of Sant’Ippolito, leading an informal tour of the stonework that decorates the city’s houses and ancient walls. She points to a keystone over a doorway and explains the carvings on its front. The grapevine in the center suggests that the people who commissioned this keystone were involved with making wine, and the letters “CD” stand for the family name. She says with pride that this work dates back to the mid 1700s.

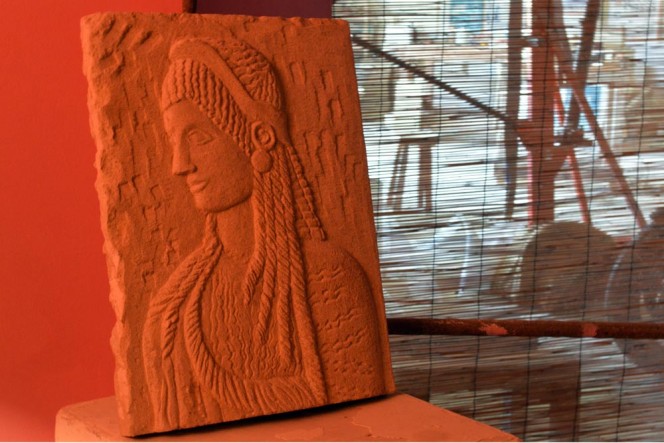

On the building’s wall just to the left of the keystone is a sculpture of a Madonna. She is intricately carved and detailed, wearing a patterned dalmatica, or dress, that is covered in stars and small crosses. And she holds her baby, as many Madonnas do. This Madonna’s eyelids are closed, the trademark characteristic of a local artist known for such sculptures.

In response to a visitor’s question, Gasparucci looks from the sculpture down at her hands. With a small smile she confirms that this is her work. While happy to show off the ancient carvings in the city, she was hesitant to point out an example of her own work that was perched less than two feet away. In fact, Gasparucci’s Madonnas can be seen adorning many homes and structures throughout the city.

Natalia Gasparucci is a stone sculptor in Sant’Ippolito, a town rooted in tradition of this art and rich with history that dates back to the 13th century.

That humility is also one of Gasparucci’s trademarks, though she has many other defining characteristics. Her short, bleached-blonde hair is dazzling in the sunlight. The creative fire inside of her is much bigger than her petite build. She is full of energy, and apparently willing to talk about anything with anyone, even people who are practically strangers. With her thick black eyeliner and Crocs almost as colorful as her personality, you’d never guess that she is a grandmother.

Gasparucci moves away from the old doorframe, takes a sharp right turn down a small hill, and passes through the open doors of her studio, Bottega Artistica Della Pietra, the Artistic Studio of Stone. It is time to continue her work.

The studio sits right outside the old walls of Sant’Ippolito, a city with centuries of stone carving history and traditions. It is also the place where Gasparucci was born and has flourished. She raised a family and still lives in the house above her studio. Sant’Ippolito was once overflowing with studios and sculptors. Today, the studio Gasparucci owns is the only one remaining within the town; only a couple of other sandstone sculptors have studios in the area.

Gasparucci picks up a chalk-covered drill and drives it through a block of pietra arenaria, sandstone, breaking off small chunks. The noisy drill overpowers the chirping of birds outside the shop doors. Her gloved hands fly in every direction. Silver bracelets on her arms clink lightly, partially covering the tattoo that stretches from the top of one wrist to the middle of her forearm, a flower with vines. Her voice reaches every corner of the large room as she explains her process. Then she brushes away the dust that has collected on top of the piece to reveal the outline of an olive branch. This piece will be a keystone.

Sant’Ippolito was once the patria, homeland, of stone carving in Italy. At its height, the city was home to more than 30 studios and many well-known sculptors. One of these artists was Amoretto, who was called from Sant’Ippolito in the 14th century to do work at the Palace of the Pope in Avignon, France.

According to Renzo Savelli, a researcher and author on the topic of scalpellini, or stonemasons, there were large quantities of high-quality sandstone in the territory around Sant’Ippolito. It was because of this kind of stone that traditions grew so strong in the area starting in the 1300s.

During the 15th century the artists in Sant’Ippolito, through their connection with Florentine sculptors, developed their techniques. The old houses that still exist in the city once belonged not to middle class citizens, but to the elite class of carvers in the city. Wealthy barons commissioned artists to create sculptures for their houses, keystones, and doorframes. Artists traded with each other—sculptures for everyday items like flour and grain.

Savelli explains that sandstone carving declined after the 17th century when marble became more fashionable. However, sandstone carving’s small flame continued to burn, and the art made a comeback in the last part of the 20th century.

Twenty-five years ago, an art professor with the help of town administrators and the Pro Loco of Sant’Ippolito, a group that organizes events for the city, picked up a project that Gasparucci has never put down. The town opened small sculpting studios, at first aimed at teaching middle school students. When the focus shifted to adults, Gasparucci was asked to sculpt in one of the studios. She and her supervisor, Luciano Biagiotti, an art professor from Urbino, were given an abandoned theater right outside of the city walls as their workspace. With this project, the stone carving traditions in Sant’Ippolito were rediscovered.

“It was just as a game,” Gasparucci says laughing, referring to the start of her sculpting career. At the time, she was concentrating on oil painting. She and Biagiotti began sculpting in the theater whenever they had time after dinner.

She was only in the old theater for a short time. Bottega Artistica Della Pietra soon became her working space and has continued to be for 23 years.

Gasparucci has filled one of the three gallery rooms connected to her working space with sculptures of the Madonna of Loreto, a famous symbol of protection for the Le Marche region and for military aviators. Madonna of Loreto has been produced in many forms. Raphael, the celebrated Renaissance painter from Urbino, has his renowned Madonna of Loreto painting in Musée Condé in Chantilly, France. Carvaggio created another famous painting of Madonna of Loreto, which hangs in Rome.

Gaparucci’s Madonna sculptures range in size, some no taller than a bottle of wine. Each is slightly different, although Gasparucci’s overall style and characteristics remain consistent.

The traditional style of Madonna of Loreto has a conic shape to her body. Gasparucci pulls inspiration from this, but sometimes sculpts the figure with her baby and sometimes without. Gasparucci combines Egyptian, Byzantine, and Mayan art in her sculptures, borrowing characteristics from each distinct style.

Some characteristics of the Madonnas are unique to Gasparucci. When the Madonna is not holding a baby, Gasparucci carves her with hands pressed together, as if praying. The faces of Gasparucci’s Madonnas also wear her unique style. Their perfectly smooth faces look peaceful and content, with soft smiles and closed eyes.

“It’s a form of sweetness,” she says about the closed eyes. “It invites you to a moment of reflection, of thinking about something.”

“The special thing about Natalia is that she not only works in the tradition of Madonna, but she introduced new subjects,” says Savelli, who is familiar with Gasparucci’s work. He explains that she is innovative; along with religious subjects, she also sculpts faces of women and men.

“She’s a great artist,” he says. “She deserves to be valued and to be known.”

Over the years, Gasparucci has been recognized for her hard work.

“My life is full of events,” she says when asked about her favorite memory or exhibition. Her work has taken her all over the globe to places like Korea, France, the United States, and every region of Italy. Gasparucci donated a sculpture to the Pope’s Palace in Avignon, France, and has been recognized with national awards. She has been interviewed by daily newspapers and popular magazines like AD, Grazia, Tutto Turismo, and Itinerari. Her work can also be found in the bank of Sant’Ippolito and many museums in the Le Marche region. One of her sculptures is in a specialized museum in Ancona, Italy, that caters to those who love art even though they can’t see it.

The director of the Museo Tattile Statale Omero, the State Tactile Museum, asked the town of Sant’Ippolito to donate a piece of art. Gasparucci sculpted Virgo Lauretana, a Madonna of Loreto holding her baby. Gasparucci explains that she spent a lot of time perfecting the details in the sculpture. She says the dalmatica had to be extra detailed, as blind people would only be able to enjoy it by touch.

Gasparucci has also donated a sculpture of Madonna of Loreto as homage to Pope John Paul II. This sculpture, presented as a gift from Gasparucci and the Le Marche region, now sits in the Vatican in Rome. Despite the world’s acknowledgement of her talent, Gasparucci remains humble.

“If I am famous, I’m still modest,” she says. “I am not so self promoting.” She says she is not driven by money so much as her passion for sculpture.

“Masterpieces only come once,” she says. Special works are linked to special feelings and states of mind, and Gasparucci says they are very different from works that are commissioned. If someone wants to purchase a work that she has a special connection to, she will not sell it.

One of these personal pieces is a sculpture of the bottom half of a face, from right underneath the nose down to the chin. The lips are plump, the mouth shaped in a serious line. In the same gallery room just behind this sculpture is another of a whole face. The chin, lips, nose, and eyebrows are visible, but the rest of the skinny features are covered in strips of stone fabric. Both sculptures were produced at important times in Gasparucci’s life, and for this reason she will never sell them.

While she still sculpts often, Gasparucci isn’t as busy with her work as she once was. She spends a lot of time with her family, particularly her grandson, Jacopo.

“Come take a photo with your poor grandmother,” she says to Jacopo during a break from her work. The five-year-old is not interested in being obedient. He is far too preoccupied with his friends playing nearby in the park. Wearing thick, black-rimmed glasses and a polo-style shirt with the collar turned up, he stomps over to Gasparucci with crossed arms. She takes his hand and proudly explains that he likes to play with her sculpting tools and leftover stone. He also asks a lot of questions about what she does.

“He’s very intelligent,” Gasparucci says.

Gasparucci starts by using a drill, but the rest she does by hand. Sculptures take anywhere from a week to 15 days.

After about 45 seconds of pleasing his grandmother, Jacopo runs back to his friends. Gasparucci puts her thick cloth gloves back on and returns to the keystone she’s been working on. Her small, fluffy white dog, Cica, finds a spot on the floor by her feet for a nap.

Instead of the loud drill, she pulls out a pointed tool and mallet. She chips away small pieces of the stone, the olive branch becoming more visible with each smack of the mallet. The afternoon sun warms the entire studio; sculptures in various stages of production reflect the rays in different ways. The only sounds are that of the mallet hitting the metal, the metal chipping the stone.

An expression of concentration takes over Gasparucci’s whole face. Her mouth forms a tight, serious line, her nose scrunched, her eyes, smudged with black eyeliner, unblinking through her glasses. She uses a brush to loosen chunks from the top of the sculpture and then runs over the smooth stone with her gloved hand. Her lips turn up into a small, satisfied smile.

Slideshow

This article also appears in Urbino Now magazine’s Urbino Centro section. You can read all the magazine articles in print by ordering a copy from MagCloud.

Order Urbino Now Magazine 2015

You can read many articles appearing on this website in Urbino Now Magazine 2015. To order a full-color, printed edition, please visit MagCloud.

You can read many articles appearing on this website in Urbino Now Magazine 2015. To order a full-color, printed edition, please visit MagCloud.Reporters

Courtney Bochicchio

Christina Botticchio

Deanna Brigandi

Alysia Burdi

Anita Chomenko

Isabella Ciano

Rachel Dale

Caroline Davis

Nathaniel Delehoy

Brittany Dierken

Sarah Eames

Thomas Fitzpatrick

Kendall Gilman

Michele Goad

Julianna Graham

Yusuf Ince

Devon Jefferson

Rachel Killmeyer

Kaitlin Kling

Abbie Latterell

Ashley Manske

Rachel Mendelson

Alyssa Mursch

Manuel Orbegozo

Dylan Orth

Olivia Parker

Katie Potter

Gerardo Simonetto

Jake Troy

Stephanie Smith

Tessa Yannone

Ryan Young

Promotional Video Project

Nicole Barattino

Richard Bozek

Rebecca Malzahn

Abigail Moore

Charlie Phillips

Story Categories

Past Urbino Projects

Read stories and view the photography and video from last year's website.

Read stories and view the photography and video from last year's website.

2013 Website

Read stories and view the photography and video from the 2013 website.

Read stories and view the photography and video from the 2013 website.

2013 Urbino Now App

Interactive Apple iPad app covering culture and travel for visitors to Urbino and Le Marche.

Interactive Apple iPad app covering culture and travel for visitors to Urbino and Le Marche.

2012 Website

Read stories and view the photography and video from the 2012 website.

Read stories and view the photography and video from the 2012 website.

2012 Urbino Now Magazine

Explore past coverage from the 2012 edition.

Read all 30 magazine articles online or visit MagCloud to order a printed copy of Urbino Now 2012.

Explore past coverage from the 2012 edition.

Read all 30 magazine articles online or visit MagCloud to order a printed copy of Urbino Now 2012.

2011 Website