A Renaissance Man in a Renaissance Town

Ivo Klaver, who studies orchids, geology, literature, and the history of science, fits right into Urbino

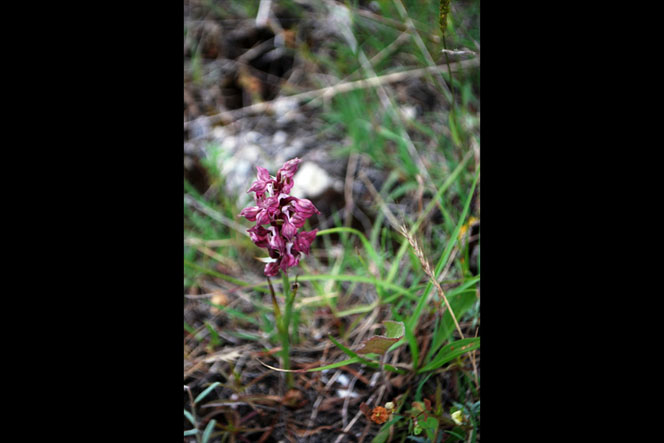

The Mediterranean sun shone down on Ivo Klaver’s face as he lifted up yet another wild orchid for me to see. “This is a bee orchid,” he said. No wonder: With six white petals and a spectacular combination of yellows, browns, and greens in its center, the flower looked just like a bee. As we continued on our hike on the outskirts of Urbino, Italy, with mountains surrounding us and a faint view of the Adriatic Sea in the horizon, Klaver explained that orchids have evolved to take on the shapes of the insects that pollinate them, to attract the insects and assure the plants’ survival.

He seemed to know everything about each orchid we saw, its species, name, and history. But, as I soon learned, Klaver also seemed to know everything about English literature, the history of science, and the 19th century. A native of the Netherlands, educated in England, and now at home in Italy, he is a Renaissance man in a Renaissance town. And orchids seem to be the common thread throughout his research.

Klaver first started studying orchids when he was a boy in Rolde, Holland. “My father grew tropical orchids in a hot house, so he was interested in orchids in general, and he showed me around when I was a lad, the wild orchids growing around at home.” His father was a biology teacher.

Klaver left home when he was 21 to get his M.A. in English Language and Literature at Exeter College in western England. He described this part of England as “good for orchids,” and began studying them during his stay at Exeter. While he was a student, Klaver bought Charles Darwin’s book Fertilisation of Orchids, which explained complex evolutionary theories of orchids and insects. As Klaver told me, “It was the first publication after On the Origin of Species to show that his theory of natural selection was working.”

After reading Darwin’s book, Klaver continued studying orchids at university. While still living in England, he became a member of the German Orchid Society, one of the largest in Europe, which publishes a journal four times a year of over 200 pages of findings and facts. After moving to Italy upon graduating school, he became part of Gruppo Italiano per la Ricerca sulle Orchidee Spontanee, or the Italian Group on Research of Wild Orchids. According to their website, G.I.R.O.S. “promotes the knowledge, study, and protection of Italian orchids” and organizes trips, conventions, conferences, and exhibitions.

Klaver’s love of orchids started to intersect with his studies when he was in university, working on a Ph.D. on the history of science and Victorian literature. After reading Darwin’s book on orchids, he noticed that about the same time Darwin wrote about the flowers, Victorian authors began describing orchids in their novels. “There was a point where my interest in orchids related to my professional interest in history of science and how the idea of evolution changed the idea of the spirit of the age of Victorians,” he said. In other words, what the Victorians thought and wrote changed greatly because of Darwin’s theories of evolution.

Klaver and I were sitting in his office across the street from Urbino’s Palazzo Ducale, built in the 15th century by another Renaissance man, Federico da Montefeltro. In the dim light, I spotted the book Klaver wrote about his findings, Geology and Religious Sentiment: The Effect of Geological Discoveries on English Society and Literature Between 1829 and 1859. His hands moved about as he described the history of the Earth, and his eyes lit up as he spoke in a serious, yet lively tone.

“In the 1830s,” he said, “geologists started to build up a new kind of discipline which becomes modern geology. They realized that the Earth was much older than was previously thought, much older than the biblical story. If you calculate back [using] the Bible, you can go back about 6,000 years to the creation of the Earth, and the geologists simply say that that is not [old enough]. The Earth is at least millions of years old.”

I began to wonder how this connected with orchids. As I should have guessed, there was more.

“Darwin writes his book on orchids to show that orchids slowly evolved into very complex mechanisms, and in order to make this possible, Darwin needed a lot of past geological time.” In other words, Darwin used the evolution of orchids to prove his theories to the Victorians. As Darwin’s theory became more accepted, the Victorians started writing about and describing orchids in their novels, making them a popular flower at the time. Orchid hunters became popular as well. In Klaver’s eyes, orchids and his research connect simply because of the flowers’ evolutionary and scientific importance in the 19th century, and because they were such a prominent part of Darwin’s theories.

Currently, Klaver is working on a project with several members of his orchid group. “What I’m working on now…here…just let me show you.” Klaver pulled out his computer and began typing vigorously, excited and eager. A Google Earth map appeared on the screen, along with hundreds of tiny red dots. “You can click on the map and get all of the distributions of the orchids in Italy and the areas around Italy,” Klaver said. “This is a huge project which should result in an atlas of the distribution of Italian orchids.”

The orchid group notes on their website that Urbino is a perfect place to study and research. More than 60 species of wild orchids have been found in the Marche region so far, and new species are still being discovered.

Likewise, Urbino is an inspiring place for Klaver to study the Victorians. In the Renaissance, as in the Victorian era, he says, “The boundaries between literature, science, and theology were often hazy.”

He adds: “I am aware of Urbino’s history every day I walk to my office.”

This article also appears in Urbino Now magazine’s La Gente section. You can read all the magazine articles in print by ordering a copy from MagCloud.