The Monuments Man of Italy

A perilous mission achieved in saving art

URBINO, Italy – On the night of October 19, 1943, as German soldiers entered the historic Palazzo dei Principi in Carpegna, a clandestine operation hung in the balance: hiding thousands of masterpieces from theft or destruction by the Nazis. The man behind the operation, art historian Pasquale Rotondi, reflected on that night in his memoir. “[The Germans] did a search in this building; the guardians, who protected this hiding place, tried to keep the soldiers from searching the rooms, where they had taken the works of art, but [many guards] were disarmed, beaten, and carried away.” The remaining guards were able to convince the soldiers that there was nothing of value to be found. The Germans left without a single masterpiece in hand.

This is just one of many close calls in the treacherous and eventually historic journey of Pasquale Rotondi. He was 31-years-old when the Italian Minister of Education commissioned him to carry out a task of great cultural significance: to hide and to preserve some of the Italy’s most prestigious artworks. As the Superintendent of the Artistic and Historic Heritage in Urbino, Rotondi was a prime candidate for the job. “The more you lay it to heart, given the importance of things, the more you can understand my concern for [the artworks’] conservation,” he wrote in his diary.

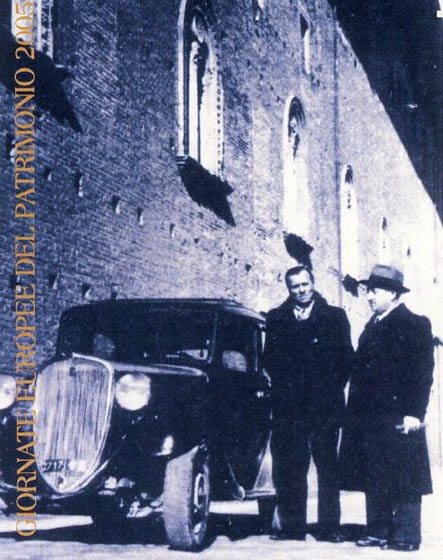

A poster showing Pasquale Rotondi and his assistant, Augusto Pritelli, with the automobile they used to shuttle thousands of artworks. This poster was featured during the European Heritage Days in 2005 at the Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana in Venice.

In the spring of 1940 Rotondi embarked upon what would become a five-year journey, hiding more than 10,000 masterpieces within fortresses located in Italian cities in the region of Marche, including Urbino and Sassocorvaro. He chose Sassocorvaro because it was located away from the war zone and had an area of fortified security — the Rock of Sassocorvaro.

The Rock of Sassocorvaro is a large walled structure overlooking a lake valley. The locals call it the “fortress of works of art,” where extraordinary masterpieces are housed to this day. It also contains a theater that served a higher purpose for Rotondi. Under the boards of the main stage, about 2,000 pieces of art were furtively stored.

The exclusive theater within the Rock of Sassocorvaro. Rotondi hid many pieces of art under the boards of this stage.

In an attempt to stay a step ahead of the German soldiers, Rotondi carefully monitored which cities had already been occupied and which ones were less likely to be searched or destroyed, including the city of Urbino. “I wanted to create in Urbino some safe hiding places where…I could take the most important works of art,” Rotondi wrote. The Palazzo Ducale became the temporary hiding place, with about 6,000 pieces stored in the cellars of the massive structure.

A view of the underground cellar in the Pulazzo Ducale. This area provided an abundant amount of space for Rotondi to store artwork.

During the course of World War II, superintendents from museums in Venice, Milan and Rome entrusted Rotondi to transfer to safekeeping their most valuable collections including masterpieces by Caravaggio, Tintoretto, Giorgione, Botticelli, Leonardo and Titian. One famous work, “The Tempest” by Giorgione, was kept, for a time, wrapped under Rotondi’s bed in his personal residence. All-in-all Rotondi meticulously and courageously saved 4,000 books, manuscripts, archives, and original music scores, as well as approximately 6,000 paintings, sculptures, tapestries, religious furnishings, and ceramics.

“The Tempest” by Giorgione (1506-1508.) The painting was originally commissioned by Venetian nobility and is now exhibited in the Gallerie dell’Accademia. Source: Diana Ziliotto

On September 8, 1943, the Italian government drew up an armistice agreement with the Allies, thereby joining the movement to force the Germans out of Italy. After the War ended, Rotondi’s entrusted artworks were returned to their original museums in Italy, includingGallerie Dell’Academia in Venice.

At the completion of the operation, Rotondi moved back to Urbino, resuming his work as Superintendent of the Artistic and Historic Heritage. In 1949 he became the Superintendent of Fine Art in Genoa, and 11-years later the director of the Central Institute of Restoration in Rome. After his retirement in 1973, the Vatican chose him as a consultant for the restoration of the Sistine Chapel.

Rotondi’s wartime mission went largely unpublicized until 1984, when the mayor of Sassocorvaro bestowed upon him an award for his work. In 1986, the City of Urbino named him an “honorary citizen,” praising his achievements in teaching and maintaining the cultural heritage of the city.

Sara Ugoloni, a tourism official for the city of Sassorcorvaro, says tourists from all over Italy visit the town’s fortress just to see one of the sites where Rotondi made history. “Local schools teach the story of Pasquale Rotondi, and many universities are interested in the story [as well,]” says Ugoloni.

After Rotondi’s death in 1991, at the age of 81, his achievements increased in recognition:

- 1997: Premio Rotondi ai Salvatori dell’Arte (Rotondi Award for Art Preservationists) was created and is awarded annually to a person who has saved art from destruction

- 1999: Salvatore Giannella published “The Ark of Art”including excerpts from Rotondi’s memoirs, and “Operation Rescue”in 2001

- 2005: Italian President Carlo Ciampi presented Rotondi’s eldest daughter with a medal honoring her father’s devotion to cultural preservation

- 2005: Documentary film “The List of Pasquale” Rotondi was released

Author Giannella concludes: “the book[s], the film, and the award constituted the stone thrown into the pond of public opinion internationally, even in Hollywood.”

Bold acts of World War II art preservation are popularized in the Hollywood film “The Monuments Men”and in the documentary “The Rape of Europa”, but Rotondi’s story is not a part of these productions.

Giannella says, “unfortunately, Rotondi was given very little immediate reward for his feat.” But Rotondi himself was not seeking financial reward for his 5-year mission. The reward, he says, was in preserving the art itself and its culture: “I’m just doing my duty as guardian of the integrity of works of art entrusted to me.”