Modern Day Da Vinci Code

Pietro Barsotti retraces Leonardo Da Vinci’s steps to help bring Urban Trekking to Urbino

Scaling the walls of the 14th century Fortezza Albornoz in mid-June presents all kinds of challenges for a visitor unaccustomed to the Mediterranean sun. But self-taught historian and Urbino native Pietro Barsotti casually wipes the beading sweat from his forehead as we head up the stairs of the structure, looking all too comfortable. “Are you ready?” he asks, barely able to contain the excitement in his voice as our tour begins.

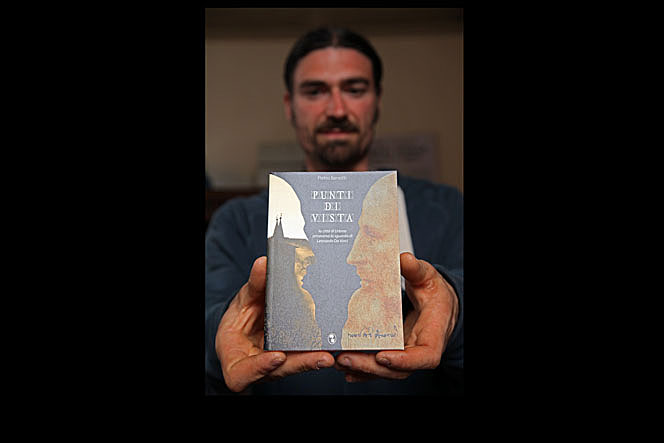

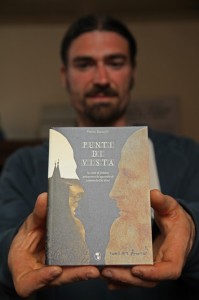

With his recently published book, Punti di Vista (Points of View), in hand Barsotti begins with a little-known fact: “In August 1502, Leonardo Da Vinci visited Urbino, staying in the Ducal Palace for the month.” Barsotti has helped to create a unique tour that takes guests through, around, and over the city, retracing Da Vinci’s steps by using as a roadmap many of the drawings he did while in Urbino.

The tour, “On the Trail of Leonardo,” is an example of a new style of tourism gaining ground across Italy. TrekkingUrbano (Urban Trekking) is an organization out of Siena whose goal, according to their website, is to bring tourists to the “most hidden and least known” culturally rich cities of the country, such as Urbino. TrekkingUrbano launched in 2013, highlighting 33 cities across Italy. More hiking than walking, Trekking tours range from easy to difficult with the longest (in Naples) at 11 kilometers and six hours. At three hours and 2 kilometers, Barsotti’s tour gets an “easy” rating—though face-to-face with Urbino’s countless steep hills and stairs, you might disagree.

During the month Da Vinci spent in Urbino, he worked for Cesare Borgia, who was Duke of Romagna at the time. As part of a systematic takeover campaign of Le Marche, Borgia, son of Pope Alexander VI, called upon Da Vinci, the best artist, mathematician, and engineer of the time, to conduct a large-scale reconnaissance mission. Da Vinci was to document all fortifying structures and defensive tactics the city had to eliminate any surprises when Borgia invaded.

“After the fall of the Milanese regime in 1499 [Da Vinci] was looking for a major patron,” says Martin Kemp, emeritus professor of the History of Art at the University of Oxford. He was in between some of his most famous works and was paid generously to serve under the Duke, during an unstable time in Italy.

Borgia sent a letter of introduction with Da Vinci certifying his credentials and giving him access to anything within the city, even allowing him to stay at the Ducal Palace. “Borgia gave him powers to commandeer men to pace out distances to make his [drawings],” Kemp says.

It is unclear whether Guidobaldo da Montefeltro, Duke of Urbino in 1502 and son of Federico da Montefeltro, was aware of the purpose of Da Vinci’s visit. Shortly after Borgia received Da Vinci’s drawings, in the fall of 1502, he attacked Urbino, which immediately surrendered, making Borgia the new Duke of Urbino.

Pietro Barsotti published his first book, Punti di Vista (Points of View), in the fall of 2013, and shortly after turned his findings on Leonardo Da Vinci into a unique and successful walking tour of Urbino.

Although unique, Urbino was one of many cities in Le Marche that Da Vinci was sent to record. “The fortification studies [of Urbino] are like ones he did in Imola [in Emilia-Romagna]… which were worked up into a brilliant map,” Kemp says.

Barsotti originally came across Da Vinci’s drawings of Urbino while working as an art and historical artifact exhibitor, gathering and displaying unique and rare art works and artifacts each month throughout the region. “I saw the drawings [at one of the exhibits] and realized that I knew these places. That’s when I started doing my research,” he says. As Barsotti is one of few to inquire about Da Vinci in Urbino, he says that he started from scratch and was surprised with how much he could find. These discoveries became the basis for his book and eventually, for the tour.

The first stop, Fortezza Albornoz, offers sprawling views of the Ducal Palace and surrounding countryside. Da Vinci’s drawings of the fort are intricate yet far from exact, and show much less than is currently here. Barsotti explains that due to structural concerns, the walls were expanded, and in the early 16th century an addition was built to offer extra protection.

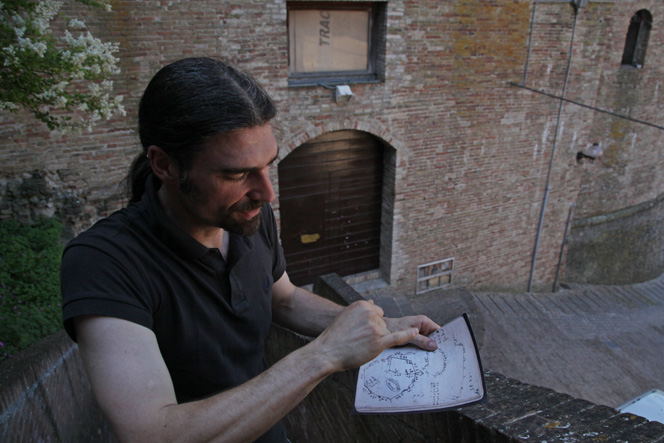

Obviously awed by the complicated drawings of the Fortezza and Urbino’s outer walls, Barsotti explains that “[Da Vinci] drew these just by what he saw. There were no measurements and he was only able to see [the city] by walking around it.”

As we move through the structure, over flimsy chain link barriers and under dilapidated wooden fences, Barsotti points to Da Vinci’s various drawings, showing our current location in relation to the images on the paper.

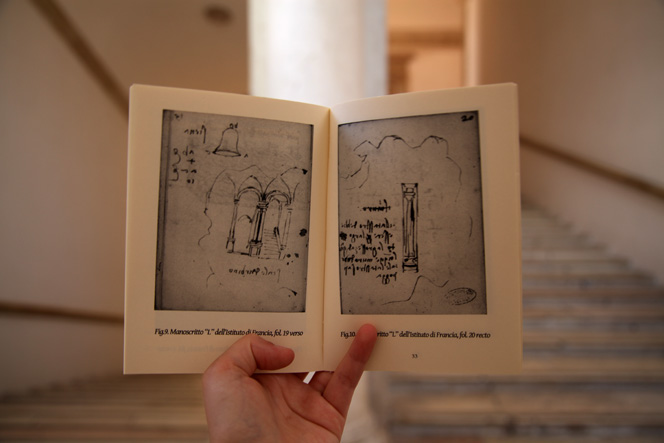

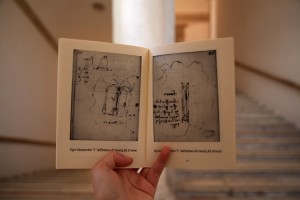

Walking along the city’s outer walls we arrive at the Ducal Palace, which holds one of the most well known sights captured in one of Da Vinci’s drawings of Urbino—the elegant main staircase of the Palace that connects the first two levels. “For many years, no one knew [which] stairs [this drawing depicted]. The drawing has been used to estimate the time that the Palace became two levels—which we now know was years before [Da Vinci’s] visit,” Barsotti says. In addition to the detailed staircase drawing, Da Vinci also sketched an impossibly small chapel that sits in a corner across from the Duke’s studiolo.

Along the outer walls of Urbino, Barsotti points to the stop where he is standing. Da Vinci had few ways to measure the structures and drew the pictures based only on what he could see.

Unlike his drawings of the Fortezza and the city’s outer walls, Da Vinci’s drawings within the Ducal Palace were for his personal interest and “reflect that he was impressed by the architecture,” Barsotti says of the artist’s temporary home. His drawings of the Palace clearly illustrate that the city left an impression on the then 51-year-old artist who had four years before finished the Last Supper and would, one year later, begin on the Mona Lisa.

Described by Trekking Urbano as an “easy,” two-kilometer walk, the tour is for any history buff who prefers the quiet and laid back Italy, untouched by millions of yearly visitors and overpriced gelato. But the best part is Barsotti. His wide eyes and quickened pace as we approach each new sight reveals obvious passion and a desire to impart his wide-ranging knowledge, something that is hard to come by among typical tour guides in bigger cities.

In October 2013 Barsotti led the tour for the first time for a crowd of more than 80. One participant was Piero Paolucci, local museum guide at the Museum of Science and Technology in Urbino. Paolucci says he likes to consider himself an expert on Urbino, but that the tour gave him a new perspective. “I saw parts of the city I had never seen before,” he says. “Even the familiar parts were different because we got to explore like we were Da Vinci.”

Paolucci says that the tour is unique and eccentric, great for tourists and even more meaningful for locals. “Some people don’t even know that he was here,” Paolucci says. “Everyone who lives in Urbino should take the tour. It gives you a much different outlook; it changes your point of view.”

Indeed, the excursion offers exactly what Barsotti’s book title suggests: a different point of view. Like a tour, “trekking” offers guests, tourists, and locals the chance to see various cultural and historical sights around the city. But trekking’s uniqueness, according to the organization’s website, is its physical aspect. Each trip offers more physical demands that simply walking around a city. Additionally, Barsotti’s trek gives participants the chance to navigate, using Da Vinci’s drawings as a map, rather than just see.

In addition to drawing the stairs, pictured on the left page, Da Vinci also had an eye for the architectural details such as the Palace’s pillars, on the right.

This was one of the main goals of Maria Francesca Crespini, Cultural Commissioner for the City of Urbino, who worked with Barsotti to develop the best tour possible after TrekkingUrbano contacted him. She says that tours allow you to the sights, but trekking transports you back in time. “We [the Department of Tourism] were happy to be chosen for these alternative cultural itineraries,” she says. “It was a very interesting proposal, to enhance even such a magical place as the Albornoz Fortress, the city’s walls, and spots within the Palace.”

This year looks promising for a second installment of Trekking Urbano in Urbino, and Crespini welcomes it. “We are looking forward to promoting the same route for 2014. Perhaps we will integrate it with other programs,” she says. As for Barsotti, he will continue his day job as an exhibitioner throughout Le Marche. He says that starting up the tour had its challenges but now he hopes to perfect it. “The first is always the most difficult,” he says. “From here hopefully they will be as rewarding and successful as the first.”

This article also appears in Urbino Now magazine’s Arte e Cultura section. You can read all the magazine articles in print by ordering a copy from MagCloud.