Life and Death in Urbino

Stepping inside the Oratorio Della Morte

Standing outside the cold metal gates, I can’t shake the feeling that I’m not supposed to be here. The street is abandoned, and the quiet is thick. My only company is the Madonna portrait framed on the opposite wall, but she offers no comfort. Peering through impenetrable metal bars, my eyes adjust to the dimly lit room on the other side. The dust in what meager sunlight is allowed here is immediately visible; but then a skeleton mounted in a black frame, and then Christ on the cross, seemingly massive in the shadows. Squinting, I eventually make out that the space before me is church-like and small, but full of emptiness. I take a step back, conceding defeat; today the answers elude me. What is in the Oratory of Death?

Over the course of the next few days, I sat in the alley where the oratory is located and waited and watched. Few passersby entered the alley, and even fewer seemed to take notice of the Oratory. One man stopped to take a few pictures; I asked if he knew anything about the Oratory. He replied, “I think this is where they brought the sick” before shrugging and walking away. It seems as though few people pay attention to or are even aware of the history of the Oratorio della Morte.

After enduring mostly futile Internet scavenging and the puzzled looks of tourists and Urbinati alike, a loose grasp on the historical context of the Oratory began to take shape. The confraternity of the Oratorio della Morte was founded in 1578 and, like all Catholic confraternities, was established to perform specific social services. This brotherhood carried out the task of transporting the dead from their homes to the church, hence the name Oratory of Death. The confraternity also provided housing for widowed women so that they would not fall into poverty or prostitution. In many ways, confraternities like this one were predecessors to the social programs implemented by modern governments. Today, the confraternity continues to offer shelter to those in need.

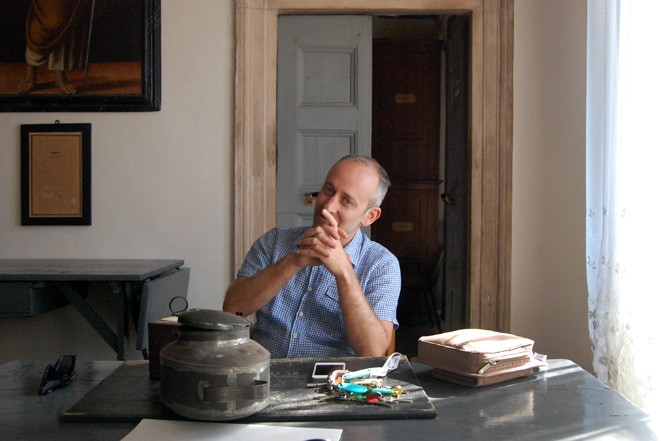

Luigi Bravi, director of the Oratory, lightens up when discussing the future of this institution, founded in 1578 to help citizens of Urbino with funerals and to care for widows.

These initial searches, however, all seemed to converge on one name: Luigi Bravi. Bravi is an apparent expert on the mysterious building, which is tucked away down a series of sidestreets that lead to, of course, a dead end. Bravi is perhaps the only known expert on the Oratorio. If there is anyone that can help me get inside, it’s him.One week later, after a series of e-mail correspondence, I meet with Bravi in a returning trip to the locked doors of the Oratorio della Morte. Entering through a more modest doorway in the same lonely alley, I follow Bravi to what seems to be a meeting room adjacent to the actual Oratory. The walls are adorned with paintings and photos that give a glimpse into the past and present of the confraternity. The names of current members are enumerated in a bronze placard, and a door marked “Archivo” stands on the far wall. The room is breezy and bright, but upon closer inspection, reveals an assortment of engraved skulls and crossbones—the symbol of the Oratory. Closer than ever, an anxiety that somehow my goal of entrance to the Oratory itself will slip away begins to creep.

Bravi sits across the table; a large set of keys placed next to his iPhone. His hair is greying but he still appears young. He responds to my questions directly and with a definite tone of authority and his answers are multifaceted, sometimes overwhelmingly informed. Simple inquiries are greeted with detailed histories, but the proximity of the Oratory continues to cast a shadow over the room.

“Fraternities are perceived as something of the past” explains Bravi, who is in fact the current director of the Oratorio della Morte, “and they are really something of the past.” The public’s lack of information is a result of several contributing factors. First, the Oratories no longer hold the kind of influence they once did. Hospitals and government institutions have obviously taken on the responsibilities of caring for the dying. Second, this Oratory fell silent for some years, still in existence but not visually active. In 2008 the brotherhood returned as a more culturally informative manifestation, performing ceremonies several times a year and offering education to those curious of the confraternity’s history. And thirdly, there is a misconception that an air of secrecy surrounds the Oratorio della Morte, which Bravi made sure to dismiss. Such ideas likely have arisen from the robes and covered faces worn by some confraternities during rituals; but it has also resulted more simply from a lack of information.

A skeleton is juxtaposed with Barocci’s crucifixion of Jesus Christ; symbols of both death and life.

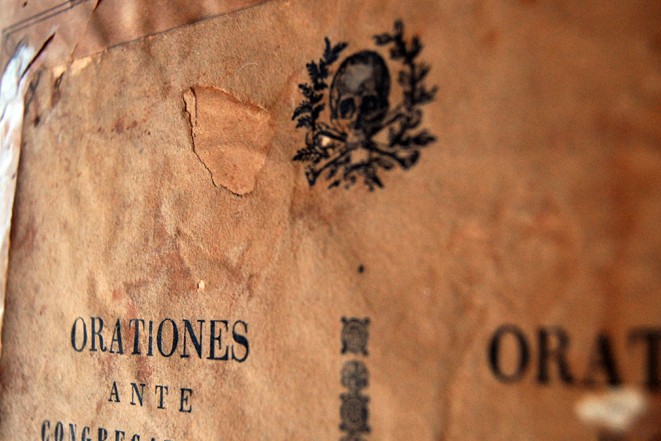

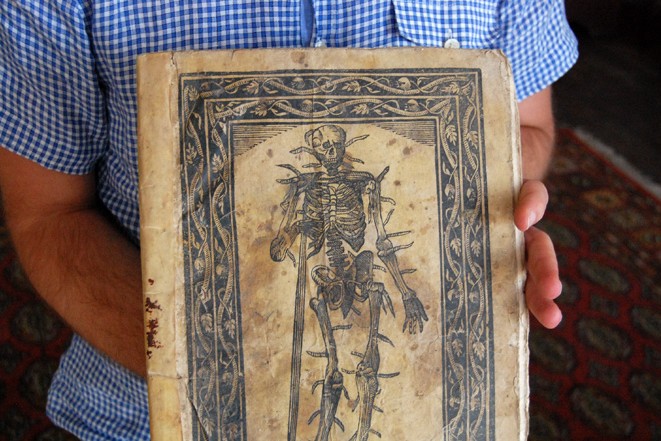

Bravi, when discussing the philosophy of the Oratorio della Morte, also made clear the distinction between ancient and modern concepts of death. After displaying a centuries old document containing the image of a thorn riddled skeleton, Bravi comments that in the past death was “something black.” However, citing the empty cross as the quintessential example, Bravi explained that the Oratory actually has developed a somewhat optimistic view of death, describing it as “full of hope.” In another painting, death, portrayed as a bony corpse, lies chained to the base of a cross, remnants of a broken scythe scattered around. “It is an opening of new doors to new life,” remarks Luigi. “Death was dead.” This idea went against my original impressions of the Oratory as being morbid or bleak. In fact, despite it’s name, the Oratorio della Morte actually has more to do with life than death.

An admittedly strategic question concerning the artwork housed in the Oratorio dell Morte finally prompts Bravi to suggest we go inside and see for ourselves. We walk down the hallway and Bravi flicks some switches before sticking an appropriately archaic, black iron key into a side entrance door. He turns the key, the door clicks resonantly, and we step inside the twilit sanctuary.

Straight ahead, rows of ornate benches colored a soft blue. The walls stretched surprisingly skyward; the whole room seemed bigger than the outside suggested. To the left, the gold framing of Federico Barocci’s massive crucifixion piece looms overhead. An organ is visible in the balcony on the opposite wall, its metal pipes arranged like a rigid set of grey teeth. The room is cool and dark, with most light pouring in from a high window. As we begin to speak again, our voices collide with the expansive walls and decorated brick flooring and echo back to us ghostlike and distant. A depiction of a skeleton with both male and female features clings to one wall. “Because death is for everyone,” Bravi says with a smile.

It is thrilling to step into a space that often is untouched, but the room maintains a certain kind of humanity. It is not difficult to imagine past incarnations of the brotherhood sitting on the wooden benches, discussing business and everyday matters. In the balcony, Luigi shares that the confraternity loves music, and that the hall is filled with voices and organ chords when meetings are in session. For a place associated with death, the Oratorio della Morte emits an unexpected sense of liveliness.

This same spirit is reflected in the archive room, which Bravi unlocks with his assortment of keys. Here, he reveals books and documents containing the business affairs and history of the confraternity that date back to the 16th century. They appear carefully preserved and maintained. ““We have to understand what we were,” Bravi would later comment. It is a somewhat bizarre feeling one experiences when absorbing the craftwork of hands that existed 500 years ago. Our time here and how we will be remembered are put into a very real context. The documents are dated up to the present day, which goes to show that the legacy of the Oratorio della Morte is still alive and taking shape.

Towards the end of our interview, I ask Bravi about one last painting, this one a portrait of Saint Francis. He shares that just recently a new discovery regarding the origins of the painting had been made, a discovery that he politely declined to indulge me with, as it has yet to be published. This was not too disappointing, as it was satisfying enough to know that there is still much to learn about the past of Urbino, especially the past of the Oratories.

“Whenever you begin to read documents, you will find something new every time—in the old,” Bravi explains, emphasizing the importance of historical research and interest. And Bravi seems optimistic about the future, joking that he does not believe the Oratorio della Morte will die anytime soon. Bravi’s motivation as director to further the heritage of this institution is, put simply, the feeling that it would be “immoral” to let the Oratory fade away, especially when there is still so much to learn. “The history of this institution is not yet finished,” Bravi concludes. And I have to believe him, for as I have seen from inside the Oratorio della Morte, in death, there is new life.

This article also appears in Urbino Now magazine’s Arte e Cultura section. You can read all the magazine articles in print by ordering a copy from MagCloud.