Story and photos by Kylie Clifton

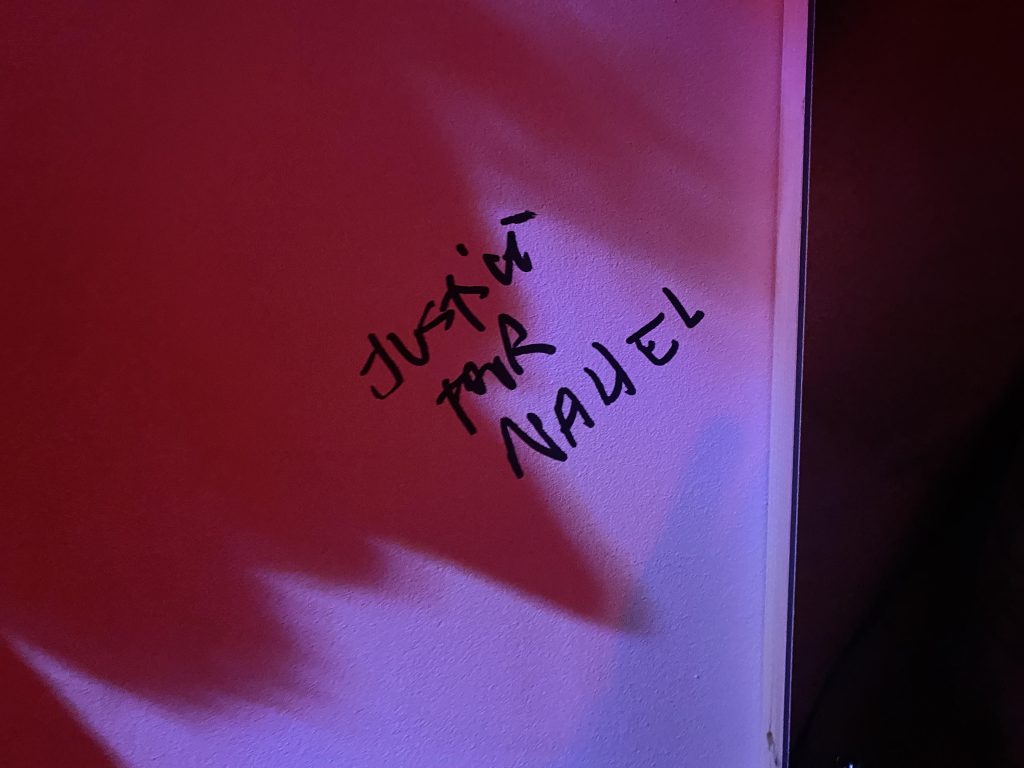

LUMA Arles is not just an art museum. Guests enter the whimsical, stainless steel-clad LUMA Tower to meet intertwining metal slides accompanied by the eerie echoes of an hourly singing exhibition composed only of sounds. The design inspires excitement and confusion alike — a theme that continues far beyond the entrance. Inside the exhibits, visitors are encouraged to touch the work as if they’re an active member in the creation.

My visit there brings to mind “Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory.” Much like Charlie’s journey in Roald Dahl’s children’s book, in which a grim reality was revealed just beyond a fanciful entrance, my troubling fate awaited me beneath a staircase, one of many unique sets of stairs, this one mirrored a double helix.

Our group of American students stood together in a tired sweat as we surrounded our English-speaking tour guide. She introduced an exhibit featuring work by Diane Arbus, an American photographer who published most of her work during the 1960s. Arbus is most recognized for her style of direct and intimate photographs of “social deviants,” which often included members of the LGBTQ+ community, drag artists, nudists and sex workers.

In introducing the exhibit, the tour guide said, “Diane Arbus’ subjects included … homosexuals and transvestites.”

My mind stopped, and I was taken back to Pride 2019 in New York City. Outside a sea of rainbow joy, transphobic protesters roared vile messages and “transvestite” was their slur of choice.

However, the tour guide’s usage was different. She wasn’t angry; she was addressing the subjects of Arbus’ work in a calm manner. I was struck. I had only heard this word paired with rage. I kept asking myself two questions: “How could this be said so casually? Is it possible they said the wrong word?”

I raised my hand, my only instrument to break the silence. “Why is it necessary to use the word transvestite?”

“Is there a different word you’d prefer?” the tour guide responded.

“Well, perhaps the word transgender or…” I offered.

Before I could finish my sentence, the tour guide told me there is a significant difference between the words transgender and transvestite. In the same breath, she said this was the language tour guides were instructed to use for a plethora of reasons — including the fact that Arbus used that word to title her works.

I knew the difference between the words and realized I should have used the word cross-dresser. The 11th edition of the GLAAD Media Reference Guide says cross-dresser has “replaced the offensive word ‘transvestite.’”

The tour guide serves as an educator and, in that role, has tremendous influence. I fear if global visitors to LUMA Arles hear a tour guide using the word, they will use it, too, without realizing how offensive it is.

This usage of this word upset me in 2019 and now again in 2023 for the same reason, but I too often forget that strangers don’t know why. I think everyone should be concerned about the usage of offensive language, but this word cuts deeper for me. I came out as transgender over eight years ago with pride and fear that still lives inside me. Today I have the privilege of “passing” as the woman that I am.

Each day I function like the entire universe knows that I am transgender. I’m always on guard, but it’s a personal battle only I’m aware of. To my knowledge, the LUMA tour guide didn’t know. This left me thinking, if she had known would she have used the word transvestite around me?

I take issue with the fact that Arbus had enormous power over her subjects. She was a cisgender white woman who was born into a wealthy family. There is a distinct power dynamic in which she held a remarkable amount of privilege over her subjects. She’s celebrated for her intimate portrayals of underrepresented subjects, but to me all of her work feels exploitative, as if she crossed a line that wasn’t hers to cross. I’m not the first to raise this issue; it was debated in her own era.

Yes, this was language that was used at the time, but the term transgender was coined in the 1960s, and people had been challenging the gender binary long before then. It’s possible that some of the drag artists Arbus photographed identified as transgender but hadn’t begun transitioning or more likely feared to start. We don’t know, but using more neutral language or even supplying context for the word would be an act of respect to Arbus’ subjects.

Instead, the conversation with the tour guide became an uncomfortable argument. This was not my intention, and as it continued, I felt the eyes of my peers with pain. What was I doing? As a proud and open trans woman, I am acutely aware of how important it is for me to speak up, but I always forget how difficult it is to do.

At the moment the group was silent, I had to excuse myself. My embarrassing fear was realized, I was the trans woman tearing up in the corner who couldn’t handle confrontation. However, I can recognize now this was not weakness, but strength.

At the close of my tour, I wanted nothing more than to leave and never be seen again. As a trans woman I yearn to be accepted in every space I enter, and often I’m the only one in the room. I wish to be able to blend in and be quiet. This time I spoke up.

After the tour, I spoke privately with the guide. She was apologetic and pledged to speak with her superiors about the use of the word. I recognize that the tour guide was not acting out of malice, but I question the attention to inclusive language in her training.

I don’t care what she titled her pieces; Arbus should not be the authority to follow.

This is a personal reflection and does not necessarily express the opinion of The Arles Project or program sponsors ieiMedia or Arles à la carte.