Photo and story by Gabriela Calvillo Alvarez

The worst part of the first day of class is introductions. I dread having to come up with five fun facts about myself on the spot to share with strangers I have yet to know. When I came to Arles for my study abroad program, it was no different. I heard one of my professors explain that we would start the lesson off that way, by getting to know each other.

She had just announced the agenda for the next few hours when she posed a question to the class about their pronouns. This part doesn’t bother me; it actually makes me feel welcome. But what I found interesting about it is that she mentioned “iel,” the gender-neutral pronoun in France.

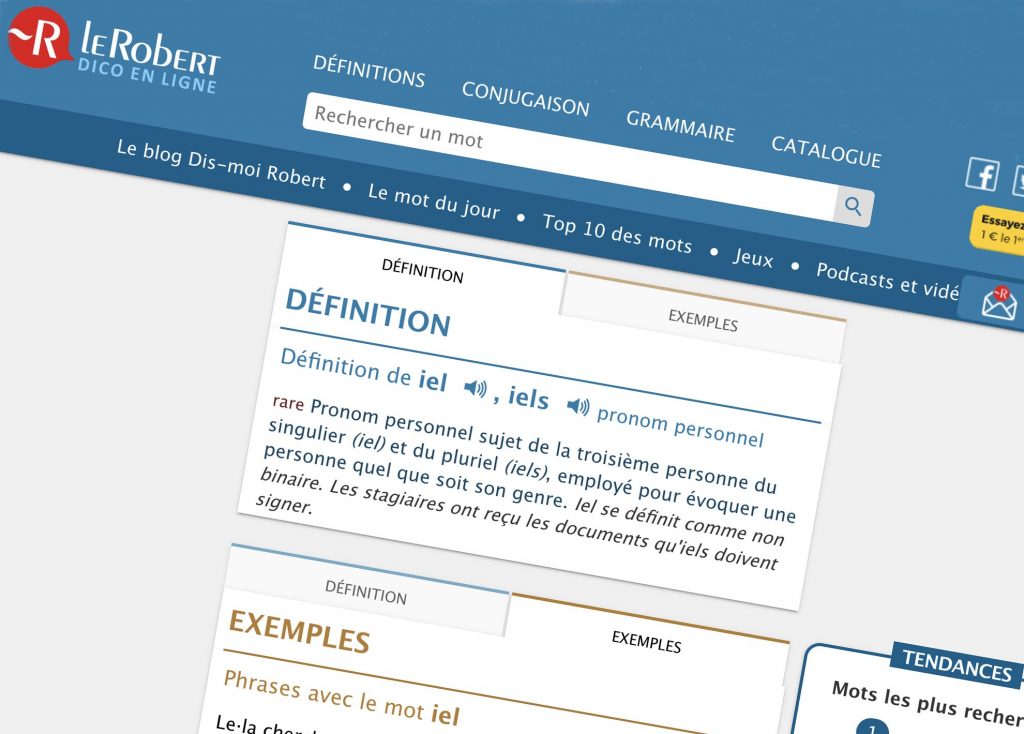

“Iel,” pronounced roughly like “yell,” combines the male (il) and female (elle) pronouns of the French language and has been a source of contention within the country for some time. Originally introduced by the online French dictionary, Le Robert, in 2021, “iel” has upset multiple people who don’t consider it a part of the language.

One of the main forces against its usage is l’Académie Française, an institution that is designed to protect the French language. One of its statutes reads: “The main function of the Academy will be to work, with all possible care and diligence, to give certain rules to our language and to make it pure, eloquent and able to deal with the arts and sciences.” As of now, “iel” is not officially approved by l’Académie.

Prior to my trip to France, I wasn’t aware that a gender-neutral pronoun existed here. I was under the impression that it would not be a popular concept. But to my surprise, it had already been a topic of conversation.

Back in 2017, l’Académie Française wrote a statement on inclusive writing, warning that “with this ‘inclusive’ aberration, the French language is now in mortal danger, which our nation is now accountable to future generations.” This kind of reaction in regards to inclusivity reminded me of a similar sentiment that many people in my own culture share.

My native tongue, Spanish, has gendered pronouns for most of the words included in everyday language. And similar to the French, the Latinx community has been having a hard time accepting gender-neutral terminology. While it has gained some traction amongst folks, many do not understand it and are afraid of what it means to the integrity of a beloved culture. Some of the older generations in my family are so enthralled with tradition that they perceive this push for inclusivity as almost a personal attack on them.

As a queer person, it’s hard for me not to feel a little alienated anywhere I go. Most of the time, I don’t force people to use they/them on me in my everyday life since I do feel comfortable with feminine pronouns. But in Arles, I have had complicated emotions surrounding gender because it feels like I have to overperform femininity to fit into the culture, both for safety and acceptance. Outside of the classroom, I’m in an entirely new environment and it’s hard to understand what is socially acceptable and what isn’t.

However, I’m glad that this conversation has begun in Arles and France generally. Perhaps Spanish-speaking cultures will follow suit. Discussions about “iel” or even “elle,” pronounced like “eh-yeh,” in the Latinx community could make way for more inclusive language in the future.

This is a personal reflection and does not necessarily express the opinion of The Arles Project or program sponsors ieiMedia or Arles à la carte.